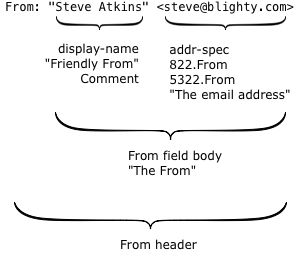

The anatomy of From:

Compared with some of the more complex pieces of the email protocol the From: header seems deceptively simple. But I’ve heard several people be confused about what it’s made up of over the past couple of months, so I thought I’d dig a bit deeper into how it’s defined and how it’s used in practice.

Here’s a simple example:

There are two interesting parts.

The first is what’s technically called the display-name, but more commonly known as the “friendly from” in the bulk email industry. It has no meaning within the email protocol, it’s just text that’s displayed to the recipient to describe who an email was sent by. Because it’s just text, you can put anything you like in there, but it’s usually either the name of the person who wrote the mail or the name of the company or brand that sent it.

The second is the actual email address, the thing with an at-sign in it. Surprisingly, this isn’t used at all during the actual delivery of the email; there’s a hidden field (called the return path or the 5321.MailFrom or the envelope sender or the bounce address) that’s used instead. For person-to-person email it’s usually the same address, but for bulk mail it’s often different.

So what does the actual email address, the 5322.From, mean? For that we go to the document that specifies what email headers mean – RFC 5322, “Internet Message Format”. (RFC 5322 is the updated replacement of the older RFC 822 – and that’s why the actual email address is often called the 822.From or 5322.From when people are being precise about exactly which email address they’re talking about).

RFC 5322 says “The From: field specifies the author of the message, that is, the mailbox of the person or system responsible for the writing of the message.” and “In all cases, the From: field SHOULD NOT contain any mailbox that does not belong to the author of the message”. It’s the email address of the author of the message.

(In some cases the email may have been written by the author, but then sent on their behalf by someone else. RFC 5322 says that in that situation the email address in the From field is still the author of the message. The person who sent the message gets their own field, “Sender:”).

What is the 5322.From used for? During the delivery process it’s used for some sorts of filtering and authentication. In particular, if you’re reading about DMARC you’ll see “identifier alignment” mentioned a lot – which basically means “the only domain we care about authenticating is the one in the 5322.From”. It’s also the usual field that’s used in user-visible mail filtering such as whitelisting email addresses that are in the users address book.

In the mail client itself the most obvious use of the 5322.From is that when you hit reply, that’s the email address your reply will go to by default. The author of the mail can override that by adding a Reply-To field, containing one or more email addresses if they want different behaviour. It’s also commonly used to filter email and to group mails by author.

What’s displayed to the end user? Originally the entire content of the From: header was shown in the recipients mailbox but it’s now fairly common to display just the friendly from, with no mention of the email address at all. That started in mobile clients, where space is at a premium and the friendly from is just, well, friendlier – but it’s spread to desktop and webmail clients too. In Yahoo webmail the 5322.From isn’t displayed anywhere at all unless you find the View Full Header menu option and dig through the raw headers, and my phone doesn’t display it anywhere obvious and only recently made it possible to see it at all.