TLS and Encryption

Yesterday I talked about STARTTLS deployment, and how it was a good thing to support to help protect the privacy of your recipients.

STARTTLS is just one aspect of protecting email from eavesdropping; encrypting traffic as the mail is being sent or read and encrypting the message itself using PGP or S/MIME are others. This table shows what approaches protect messages at different stages of the messages life:

[table nl=”~”]

Compromise point,SUBMIT~+IMAPS,TLS,PGP /~SMIME

Sender’s computer as mail is sent,,,

Sender’s computer later,,,[icon name=check-square]

Sender’s network,[icon name=check-square],,[icon name=check-square]

Sender’s ISP,,,[icon name=check-square]

Global Internet (passive),,[icon name=check-square],[icon name=check-square]

Global Internet (active),,[icon name=question-circle],[icon name=check-square]

Global Internet (later),,[icon name=question-circle],[icon name=check-square]

3rd party mail services,,,[icon name=check-square]

Recipient’s ISP,,,[icon name=check-square]

Recipient’s network,[icon name=check-square],,[icon name=check-square]

Recipient’s computer as mail is read,,,

Recipient’s computer later,,,[icon name=check-square]

[/table]

You can see that if you’re sending really sensitive data, you should be encrypting the entire message with PGP or S/MIME (or not sending the message via email at all). Doing so will protect the content of the mail against pretty most sorts of attack, but is pretty intrusive for the sender and recipient so can’t really be used without prior agreement with the recipient.

The other approaches will make some sorts of passive surveillance much more difficult, though.

Encrypting the connection a user uses to send mail ([rfc 6409]using the SUBMIT protocol[/rfc]) and to read mail ([rfc 2595]using TLS to protect IMAP or POP3[/rfc]) will protect against passive sniffing when the user is on possibly hostile network, such as public wifi or an employers network. That’s an easy place to try and sniff traffic, and if that traffic isn’t protected an attacker can not only read someone’s email, they can steal their credentials and cause all sorts of havoc. All general purpose mail clients and all ISPs support encryption here, so it’s almost universally used.

STARTTLS use with SMTP is all about protecting email traffic when it’s being sent between ISPs – both between the sender’s ISP and the recipient’s and also between any 3rd party mail services (outsourced spam filtering, mailing list providers, vanity domain fowarders, etc.).

I’ve listed three different sorts of attack on that inter-ISP traffic – passive, active and “later”.

A passive attack is where the attacker has the ability to listen to bytes as they go by, but isn’t able to modify or intercept them. While you might think of this as something a nation state would do, via secret agreements with backbone providers or high-tech fiber optic cable taps, there are ways a smaller attacker might be able to compromise an intermediate router and tap that traffic with little risk of detection. Deploying any sort of STARTTLS will protect against this, even if it’s misconfigured, using expired certificates or even just the default setup of a newly deployed mailserver. Facebook describe these weaker forms of STARTTLS as “opportunistic” in their survey – it’s not perfect, but it’s a lot better than nothing.

An active attack is one where the attacker has the ability to intercept and modify traffic between the two ISPs. This seems like it would be harder to do than a passive attack, but it’s often easier, though not as stealthy. Once that’s done, the attacker can pretend to be the recipient ISP and have full access to read, modify or discard messages. To protect against this sort of attack TLS needs to be used not just to encrypt the traffic in-flight, but also to allow the sender to validate that the mailserver they’re talking to really is who they think it is. This is what Facebook describe as “strict” – it requires that the mailserver have a valid certificate, issued by a legitimate certification authority for the domain that the mail is being sent to.

What about “later”? It’s easy to imagine a case where an attacker has been passively monitoring and recording encrypted traffic for a while, and then later they manage to acquire the encryption keys that were used (by, for example, issuing a subpoena to the recipient ISP, or using a compromise to rip them out of your servers memory). With many forms of encryption once you have those private keys it’s possible to decrypt all the traffic you’ve already captured. There are a few algorithms, though, that have what’s known as perfect forward secrecy – knowing the private keys that were used at the time the mail was transferred doesn’t allow you to decrypt them at a later time. If you’re concerned about the privacy of your messages, you should definitely read up on how to set that up.

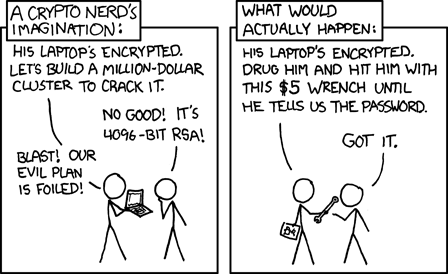

All of these techniques are a great way to defend against ubiquitous or casual attempts to read your messages, but none of them are proof against a determined attacker. If all else fails, there’s always a wrench attack.