Alice and Bob and PGP Keys

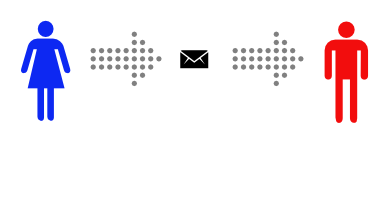

Last week Alice and Bob showed how to cryptographically sign messages so that the recipient can be sure that the message came from the purported sender and hasn’t been forged by a third party. They can only do that if they can securely retrieve the senders public key – which means they need to retrieve it from the actual sender, rather than an impostor, and be sure it’s not tampered with en route. How does this work in practice?

If I want to send someone an encrypted email, or I want to verify that a signed email I received from them is valid, I need a copy of their public key (almost certainly their PGP key, in practice). Perhaps I retrieve it from their website, or from a copy they’ve sent me in the past, or even from a public keyserver. Depending on how I retrieved the key, and how confident I need to be about the key ownership, I might want to double check that the key belongs to who I think it does. I can check that using the fingerprint of the key.

A key fingerprint looks like this:

pub 4096R/856DCBBC 2014-09-22 [expires: 2024-09-19] Key fingerprint = 7393 3400 738B ABFD 3C7A 4F31 B3E7 BD58 856D CBBC

uid Steve Atkins <steve@wordtothewise.com>

I can call my correspondent on the ‘phone to check that the fingerprint of the key I have matches their key, or check the fingerprint against somewhere they’ve published it, maybe a public blog post, or on their business card:![]()

Another option is to use a service like keybase.io, which allow people to connect their keys to their online or social media presence, and provides some tools to make using PGP less user-hostile.

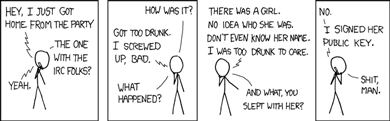

If this all seems a bit ad hoc to you, you’re right. The original approach PGP used was a web-of-trust, where you’d nominate people whose public keys you had, and you knew, as trusted or partially trusted. If someone was introduced to you, and their public key was vouched for by some configurable number of people you trusted then you’d believe that the key belonged to them. Combine that with key-signing-parties (which aren’t as exciting as they sound, just a bunch of people getting together to vouch for each others PGP keys), and you end up with a decentralized approach that sounds wonderful to an introverted crypto-nerd, and works well enough within small groups, but isn’t attractive to enough people to be able to take advantage of the network effect to break out beyond those small cliques. Web-of-trust requires far too much work and advance planning to be convenient for casual use of encrypted email other than amongst small groups of crypto-nerd friends, yet isn’t really secure enough to rely on where it’s important.

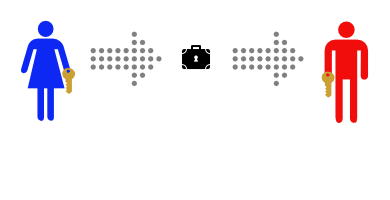

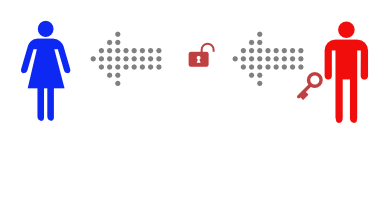

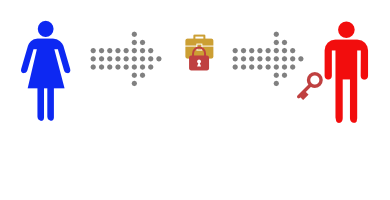

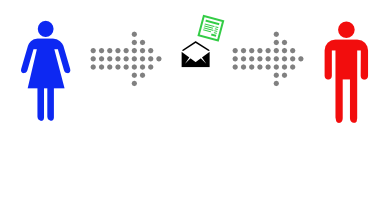

Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.

Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.