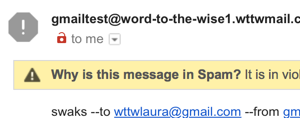

Gmail showing authentication info

Yesterday Gmail announced on their blog they would be pushing out some new UI to users to show the authentication and encryption status of email. They are trying to make email safer.

There are a number of blog posts on WttW for background and more information.

The short version is that TLS is encryption of the email between the sending server and the receiving server. It means mail can’t be intercepted or changed while between one server and another.

Gmail is now showing users whether a mail was sent using TLS.

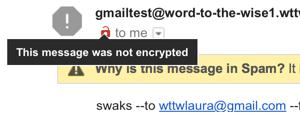

If a message is sent without using TLS, there is an open red lock shown.

If you hover over the open red lock, Gmail tells you the “message was not encrypted”

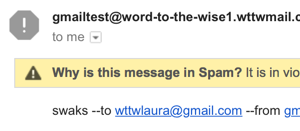

Using TLS removes the open red lock.

These messages went to spam because, well, do you know how hard it is to find a mail server that’s not authenticated? I ended up sending using SWAKS from one of our VMs so I could control a whole bunch of things, including whether or not mail used TLS. Interestingly enough, Gmail was happy to accept the mail over IPv6 but temp failed anything I sent over IPv4.

Gmail is, apparently, also notifying if mail being sent is going to a recipient on a server not using TLS. I don’t have an easy way to test that.