Comodo, TLS certificates and business ethics

We run a lot of our own infrastructure at Word to the Wise. Our email and web presence runs on our own hardware, in our own cabinet in our own network space. Partly that’s because we’re all from very technical backgrounds, and can run them in a way that’s better suited to our needs than an off-the-shelf web service. Partly it’s so we can do things like add instrumentation to our inbound mail stream so we have easy access to information when diagnosing a customer’s delivery issues. But it’s also partly so we can keep up to date on protocols and software, and leaven our advice to clients with some first hand, real world experience.

One of those things is TLS certificates, for webservers and email servers.

We already used Comodo for code-signing certificates, so when their sales rep called me and offered some decent pricing of extended validation (EV or “green bar”) certificates in exchange for a three-year commitment that seemed like a good opportunity to experience the extended validation process.

I’ve written previously about how painful the process of getting a TLS certificate from a legacy certification authority such as Comodo is, but this post isn’t about that.

I mentioned a few months ago that our green bar TLS certificate would be going away. That was because Comodo didn’t honor their agreement with us. While we ordered three years of EV certificate from Comodo, paid them for three years of EV certificate and confirmed in writing with the sales rep that they would provide three years of EV certificate, after one year Comodo decided that they wouldn’t honor that agreement.

The sales rep was mysteriously “no longer with the company” and his sales manager decided that they’d keep the money, but not provide the agreed to certificates. After a dozen or so promised calls back or email replies from a “sales manager” to discuss “what they could do for us” didn’t happen, we gave up on Comodo and switched to using Lets Encrypt for our TLS certificates.

We’re very, very happy with Let’s Encrypt. The price of “free” is nice, but it’s the simplicity, reliability and general lack of having to deal with horrible sales reps that’s the best thing.

Apparently a lot of other Comodo customers thought the same thing, as Comodo seems to want to recapture those customers by pretending to be Let’s Encrypt. They filed trademark registrations for “Let’s Encrypt”, “Comodo Let’s Encrypt” and “Let’s Encrypt with Comodo”. Comodo is in the business of “trust” and “identity” and I can’t think of any behaviour of theirs more antithetical to that.

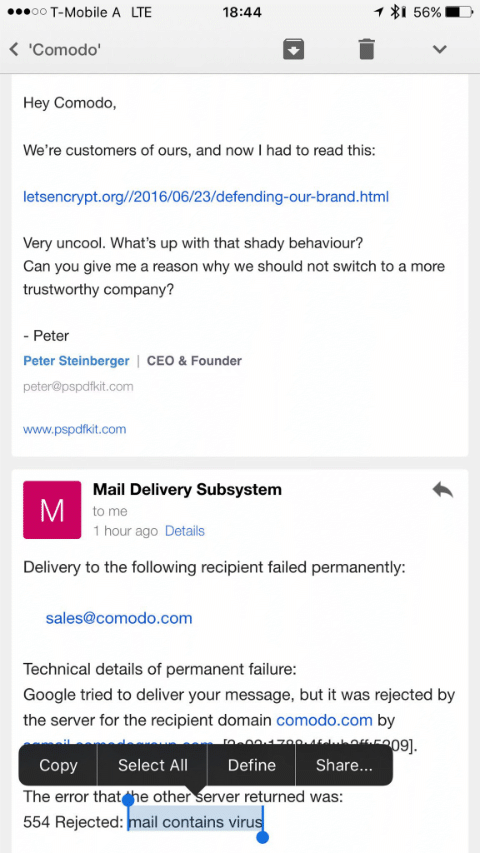

And, on an email note, Comodo also seemed to decide that they didn’t want their employees to know about this, nor to answer questions about it, and reportedly configured their email filters to reject email mentioning letsencrypt.org with “mail contains a virus”.

— from Peter Stenberger, on twitter

(Given Comodo are a major email filter vendor I hope that that’s just a local configuration used by Comodo themselves, not part of their public filtering products.)

We will no longer be using or recommending Comodo as a vendor.

(This post brought to you as an exercise in avoiding the question “What effect will brexit have on the email industry?”, as the answer “Global economic collapse would probably be bad for the email industry, yes.” seems a little simplistic.)