The twilight of /8s

A “/8” is a block of 16,777,214 usable IP addresses. That’s a big fraction of the entire IPv4 address space – about 1/224, in fact. Each one is all the addresses that begin with a given number: 10.0.0.0/8 is all the IP addresses that begin with “10.”, “184.0.0.0/8” (or “184/8” for short) is all the IP addresses that begin with “184.” and so on.

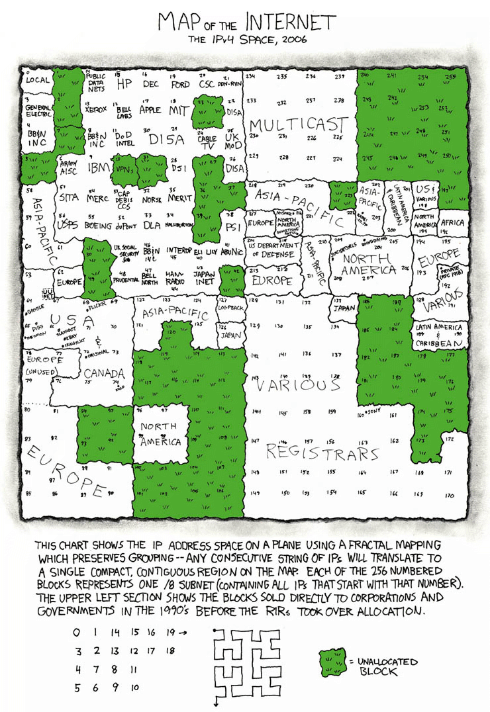

How are they used? You can see in this map of the entire IPv4 Internet as of 2006.

In the early days of the Internet /8s were given out directly to large organizations. If you look near the middle-top of the map, just left of “MULTICAST” and above “DISA” you can see “MIT”.

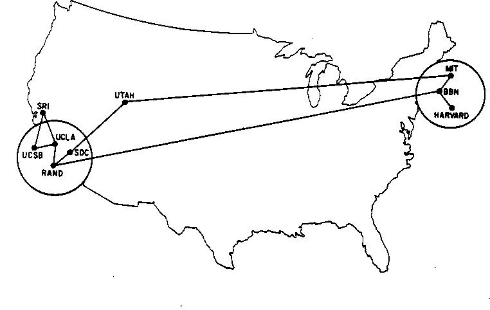

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology got into the Internet game pretty early. This is the first map I have where they appear, in June 1970:

The Laboratory for Computer Science at MIT were assigned the 18.0.0.0/8 block sometime around 1977, according to RFC 739, though it looks like they may have been using it since at least 1976.

By 1983 (RFC 820) it belonged to the whole of MIT, rather just the CS Lab, though you have to wonder how long term that was supposed to be, given the block was named “MIT-TEMP” by 1983 (RFC 870). According to @fanf (who you should follow) it was still described as temporary until at least the 1990s.

But no longer. MIT is upgrading much of their network to IPv6, and they’ve found that fourteen million of their sixteen million addresses haven’t been used, so they’re consolidating their use and selling off eight million of them, half of their /8. Thanks, MIT.

Who else is still sitting on /8s? The military, mostly US, have 13. US Tech companies have 5. Telcos have 4. Ford and Daimler have one each. The US Post Office, Prudential Securities, and Societe Internationale de Telecommunications Aeronautiques each have one too.

One is set aside for use by amateur radio.

And two belong to you.

10.0.0.0/8 is set aside by RFC 1918 for private use, so you can use it – along with 192.168.0.0/16 and 172.160.0.0/12 – on your home network or behind your corporate NAT.

And the whole of 127.0.0.0/8 is set aside for the local address of your computer. You might use 127.0.0.1 most of the time for that, but there are 16,777,213 other addresses you could use instead if you want some variety. Go on, treat yourself, they’re all assigned to you.