Using SSL TLS to protect data in transit and authenticate servers you contacted originally required specialized software, complex configuration and expensive and complicated to require certificates.

The need for specialized software is long since gone. Pretty much every web server and mail server will support SSL out of the box.

Basic server configuration is now pretty simple – give the server a couple of files, one containing the TLS certificate and the other the associated private key. (Configuring a server securely, avoiding a variety of attacks on weak parts of the SSL/TLS protocol, can be a bit more work, but there are a lot of tools and documentation to help with that).

But acquiring a certificate from a reputable provider is still expensive enough (one Certificate Authority’s list price for entry level certificates is $77/year, though the same certificates are available for <$10/year from resellers, which tells you a lot about the SSL certificate market) that you might not want to buy one for every endpoint.

And the process of buying an SSL certificate is horrible.

First you have to find a Certificate Authority or, more likely, a cheap reseller. Then it requires generating a “Certificate Signing Request” – something that can be done in dozens of different ways, depending on the device it’s being generated for. The user-friendliest way I’ve found to do it is to use the openssl commandline tools – and that’s really, really not very friendly.

Then you need to log in to the CA, upload the CSR, follow a bunch of directions to confirm that you are who you say you are and you’re entitled to a certificate for the domain you’re asking for. That can be as simple uploading a file to a webserver that serves the domain you’re getting a certificate for. Or it can turn into an inquisition, where the CA requires your home address and personal phone number before they’ll even talk to you.

Then you need to use the same browser you submitted the CSR request from to get your certificate – as the CA doesn’t do all the cryptography itself, it relies on your web browser for some of it. There are some security-related reasons why they chose to do that, but it makes for a fragile – and near impossible to automate – process. And the attempts to upsell you to worthless “security” products are never-ending.

There’s probably more horribleness, but it’s 9 months since I last bought a certificate and I may have forced myself to forget some of the horror.

There’s no need for it to be that painful. It’s easy to mechanically prove to a Certificate Authority that you control a domain in the same way you prove ownership to other companies – put a file the CA gives you onto the webserver, or add a special CNAME to your DNS.

And once you’ve proved you own a domain a certificate for that domain could be generated completely automatically. For the most common web setups you could even prove domain ownership, generate a new certificate and install that certificate into the webserver entirely automatically.

I’m sure there’s some reason other than “because we’re milking the SSL cash cow for all it’s worth” that dealing with most Certificate Authorities is so painful and expensive. But there’s no need for them to be that way.

This year there’ve been several groups who have stepped forward to escape the pain of dealing with legacy Certificate Authorities, at least for basic domain verified TLS certificates (as opposed to the “green bar” extended verification certificates you might want for, e.g. an eCommerce site).

Lets Encrypt has been one of the higher profile new CAs who are driving this effort. With the help of ACME, an open protocol being developed for issuing certificates automatically, they’re providing zero-cost TLS certificates. They’re hoping that, to use their phrase, you’ll encrypt everything, using TLS to encrypt traffic everywhere it makes sense to do so.

So, how does it work?

It works wonderfully well.

Lets Encrypt is still in public beta testing for a few more weeks, but I just got beta access. Installing their client tool on a reasonably recent Linux box just took copy-pasting two commands and waiting a minute.

The tool supports a variety of different ways to request a certificate – from entirely automated for a vanilla Apache installation through to the most complicated, entirely manual.

To see how difficult it was I decided to install a certificate for blighty.com, a domain on one of our very old webservers – one that was too old to install the letsencrypt tool itself. Fully manual! For a website on a different server!

I ran the letsencrypt tool, telling it I wanted a certificate for blighty.com. It gave me a the contents and location of a file to put on the blighty.com webserver – creating that required copying and pasting two commands from one shell window to another. Then it created and gave me the new certificate and key. I copied those across to the webserver and reloaded it’s configuration. And I have TLS!

This is going to be very simple to completely automate, so you could easily build it in to existing automation to create TLS protected action and tracking links for branded domains. Supporting thousands of TLS protected hostnames wouldn’t be difficult.

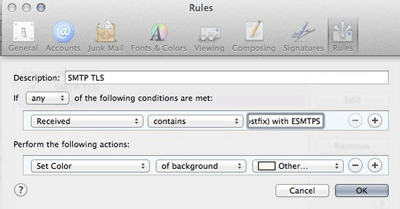

And how about using the certificates for things other than webservers? Mail servers, say? You do need a webserver to be live while you’re generating or renewing a certificate – but that’s actually easier to do for a host that doesn’t usually serve web pages than one that does. Once the certificate is generated you can use it for any service, including mail servers.

Read More