SPF and TXT records and Go

A few days ago Laura noticed a bug in one of our in-house tools – it was sometimes marking an email as SPF Neutral when it should have been a valid SPF pass. I got around to debugging it today and traced it back to a bug in the Go standard library.

A DNS TXT record seems pretty simple. You lookup a hostname, you get some strings back. Those strings can be used for all sorts of things, but one of them is to store SPF records – you can recognize a TXT record being used for that because the string returned starts with “v=spf1”

In reality it’s a little more complicated than that, though. You might get multiple TXT records back in response to a single query. And each of those TXT records might contain multiple strings.

Because of the way TXT records are implemented each string in one can be no more than 255 characters long. If your SPF record is longer than that you can split it into multiple fragments – usually just two, as you want to keep the whole DNS response less than 512 bytes – and the SPF checker will join all those fragments into a single string before parsing it as an SPF record.

(It joins them together without any extra spaces, so don’t do this: “v=spf1 ip4:10.11.12.13” “ip4:192.168.100.12“. The SPF checker would join those two strings into “v=spf1 ip4:10.11.12.13ip4:192.168.100.12”, which wouldn’t be valid. Doing this isn’t an uncommon mistake.)

The relevant SPF record was … take a deep breath …

“v=spf1 ip4:64.132.92.0/24 ip4:64.132.88.0/23 ip4:66.231.80.0/20 ip4:68.232.192.0/20 ip4:199.122.120.0/21 ip4:207.67.38.0/24 ” “ip4:207.67.98.192/27 ip4:207.250.68.0/24 ip4:209.43.22.0/28 ip4:198.245.80.0/20 ip4:136.147.128.0/20 ip4:136.147.176.0/20 ip4:13.111.0.0/16 ip4:13.111.64.0/24 ip4:13.111.65.0/24 -all“

You can see that’s split into two fragments. Any mail coming from an IP address in the second fragment was failing SPF (according to the SPF library I was using). Why?

The Go library call to look up a TXT record is, reasonably enough, net.LookupTXT(). It returns a list of strings ([]string, in Go-speak).

The SPF code then iterates through each string and throws away anything that doesn’t start with “v=SPF1”, as there’s often all sorts of non-SPF TXT records in a domain. Then it parses what’s left and makes a decision as to whether the mail matches the SPF record or not.

That was fine as net.LookupTXT() would return one string for each TXT record, containing all the strings concatenated together, perfect for SPF.

But in a recent Go release (1.11.0) someone changed that function so that instead of returning one string containing both fragments joined together, it returned two strings, each containing one fragment.

The SPF checker saw the first string started with “v=SPF1” and treated it as valid, but the second string didn’t so the SPF checker threw it away. So only emails that were from IP addresses in the first fragment were considered valid.

net.LookupTXT() has been fixed in Go 1.11.1, so I updated my compiler, rebuilt the code and the bug went away.

But only seeing the first fragment of a TXT record isn’t an implausible bug. I’m going to bear it in mind when I’m trying to work out why something that’s obviously valid is failing SPF at an obscure destination.

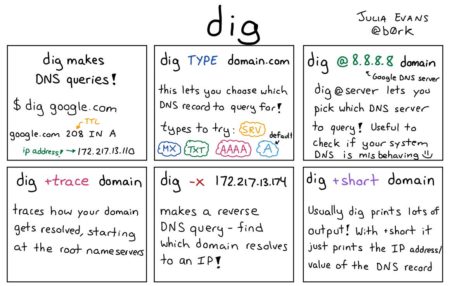

(only tangentially related to SPF, but it’s a great infographic I saw today)