Captchas

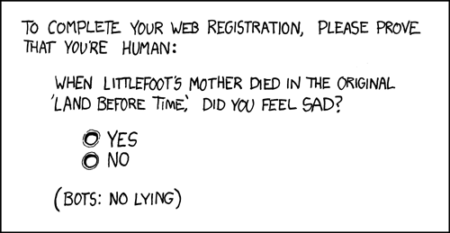

Captchas – those twisty distorted words you have to decipher and type in to access a website – have been around since the 1990s. Their original purpose was to tell the difference between a human user and an automated system, by requiring the user to answer a challenge – one that was supposedly hard for computers to solve, but easy for humans. A few years later they acquired the name CAPTCHA, an acronym for “Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart”.

Optical character recognition was pretty inaccurate in the 90s, especially with blurry or misaligned text. Text that was clearly legible to a human was completely inscrutable to state of the art OCR software. The first developers of CAPTCHA took all the advice for getting accurate OCR scans, and did the opposite – intentionally creating text that would be readable, but impossible for OCR to parse. This worked fairly well to differentiate humans and robots for a while, but eventually technology began to catch up. Off the shelf OCR got better, and mechanical attacks specific to commonly used CAPTCHAs were getting good enough to answer a significant fraction correctly.

Attempting to combat that by making CAPTCHAs harder to solve mechanically also made them much harder for humans to solve, and was terrible for accessibility. That arms race had gone about as far as it could.

Meanwhile, a group at CMU realized that the millions of hours of human time wasted by solving CAPTCHAs could be applied to do useful work instead. They had a lot of scanned documents they wanted to digiitize, but the quality of the images was too poor to OCR. So they mechanically extracted single words from the documents and showed them, two at a time, to users as a CAPTCHA and asked them to enter the two words. They knew the right answer for one word, so if the user entered that word right they’d assume they probably got the unknown word right too (and, almost as an aside, allowed the user access). That was “reCAPTCHA”.

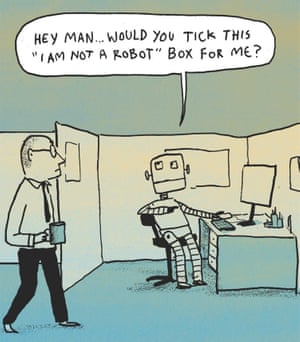

By making reCAPTCHA a hosted service it became much simpler for website owners to use CAPTCHAs, so they began to be used more widely. reCAPTCHA was acquired by Google in 2009 and they kept developing it. They used it to digitize street numbers for Google street view, and added “pick matching images” as an alternative puzzle. Increasingly, though, they didn’t actually need the humans to solve puzzles in the common case – they could tell from the history of the connecting IP address and the behaviour of the web browser that a user was likely legitimate, and let them through without making them do anything other than check a box. It was tracking reputation instead.

If you’ve ever used TOR – the secure browser that hides any identifying cookies and mixes your web traffic untraceably in with other TOR users you’ll have seen what the web looks like to users with a poor reputation. Every time you see a reCAPTCHA it’s not just a simple checkbox, it’s answering dozens of visual puzzles. That’s what most bots will see with reCAPTCHA.

reCAPTCHA is no longer really based on separating humans from bots so much as it’s differentiating between “normal”, “good” users – probably human – and “bad” users – probably bots – based on many characteristics of the users session. It’s really pretty good at that, and with the “just check a box” version of reCAPTCHA most users will see most of the time it’s pretty low friction. It’s probably the most effective tool against subscription bombing at the moment.

Google have just released version 3 of reCAPTCHA. This isn’t really a CAPTCHA at all, rather it’s a way to track the behaviour and reputation of users as visible to Google. It watches your users as they interact with your site, sends all that data to Google and they provide a quality score for each user that you can combine with your own information about them to make decisions.

It’s all very low friction, and probably very effective at detecting malicious bots. But it’s also a very intrusive user tracking technology that’ll send user history to Google whenever they’re on a site that uses it. The list of information it captures is definitely enough to uniquely fingerprint and track a user. It’ll be interesting to see what happens when that collides with the move towards web browsers being more privacy-focused and hostile to tracking.