Cryptography

Alice and Bob and PGP Keys

- steve

- Sep 24, 2014

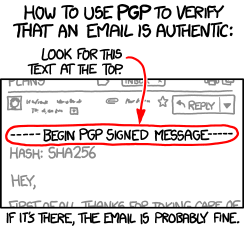

Last week Alice and Bob showed how to cryptographically sign messages so that the recipient can be sure that the message came from the purported sender and hasn’t been forged by a third party. They can only do that if they can securely retrieve the senders public key – which means they need to retrieve it from the actual sender, rather than an impostor, and be sure it’s not tampered with en route. How does this work in practice?

If I want to send someone an encrypted email, or I want to verify that a signed email I received from them is valid, I need a copy of their public key (almost certainly their PGP key, in practice). Perhaps I retrieve it from their website, or from a copy they’ve sent me in the past, or even from a public keyserver. Depending on how I retrieved the key, and how confident I need to be about the key ownership, I might want to double check that the key belongs to who I think it does. I can check that using the fingerprint of the key.

A key fingerprint looks like this:

Alice and Bob Sign Messages

- steve

- Sep 19, 2014

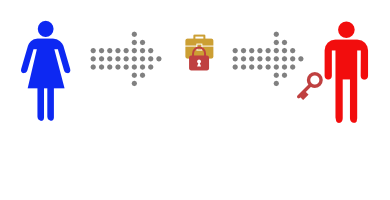

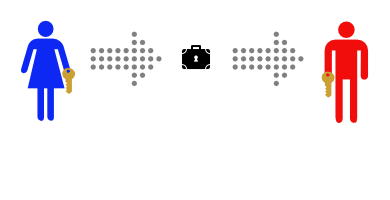

Alice and Bob can send messages privately via a nosy postman, but how does Bob know that a message he receives is really from Alice, rather than from the postman pretending to be Alice?

If they’re using symmetric-key encryption, and Bob is sure that he was talking to Alice when they exchanged keys, then he already knows that the mail is from Alice – as only he and Alice have the keys that are used to encrypt and decrypt messages, so if Bob can decrypt the message, he knows that either he or Alice encrypted it. But that’s not always possible, especially if Alice and Bob haven’t met.

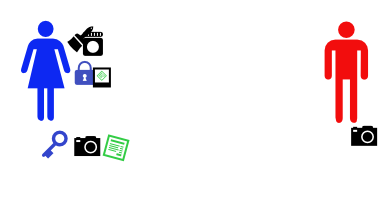

Alice’s shopping list is longer for signing messages than for encrypting them (and the cryptography to real world metaphors more strained). She buys some identical keys, and matching padlocks, some glue and a camera. The camera isn’t a great camera – funhouse mirror lens, bad instagram filters, 1970s era polaroid film – so if you take a photo of a message you can’t read the message from the photo. Bob also buys an identical camera.

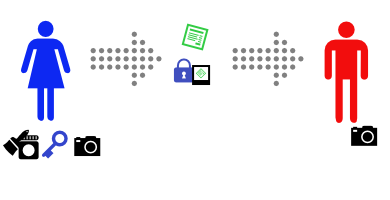

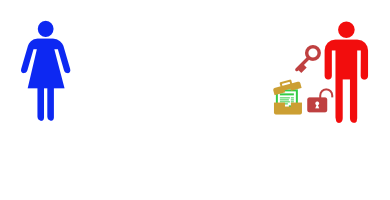

Alice takes a photo of the message.

Then Alice glues the photo to one of her padlocks.

Alice sends the message, and the padlock-glued-to-photo to Bob.

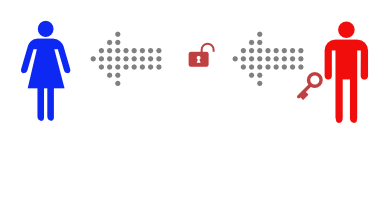

Bob sees that the message claims to come from Alice, so he asks Alice for her key.

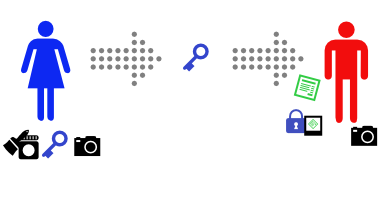

(If you’re paying attention, you’ll see a problem with this step…)

Bob uses Alice’s key to open the padlock. It opens (and, to keep things simple, breaks).

Bob then takes a photo of the message with his camera, and compares it with the one glued to the padlock. It’s identical.

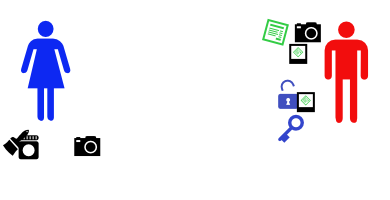

Because Alice’s key opens the padlock, Bob knows that the padlock came from Alice. Because the photo is attached to the padlock, he knows that the attached photo came from Alice. And because the photo Bob took of the message is identical to the attached photo, Bob knows that the message came from Alice.

This is how real world public-key authentication is often done.

Cryptography with Alice and Bob

- steve

- Sep 17, 2014

Untrusted Communication Channels

This is a story about Alice and Bob.

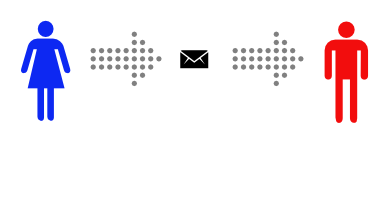

Alice wants to send a private message to Bob, and the only easy way they have to communicate is via postal mail.

Unfortunately, Alice is pretty sure that the postman is reading the mail she sends.

That makes Alice sad, so she decides to find a way to send messages to Bob without anyone else being able to read them.

Symmetric-Key Encryption

Alice decides to put the message inside a lockbox, then mail the box to Bob. She buys a lockbox and two identical keys to open it. But then she realizes she can’t send the key to open the box to Bob via mail, as the mailman might open that package and take a copy of the key.

Instead, Alice arranges to meet Bob at a nearby bar to give him one of the keys. It’s inconvenient, but she only has to do it once.

After Alice gets home she uses her key to lock her message into the lockbox. Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.

Then she sends the lockbox to Bob. The mailman could look at the outside, or even throw the box away so Bob doesn’t get the message – but there’s no way he can read the message, as he has no way of opening the lockbox.

Bob can use his identical key to unlock the lockbox and read the message.

This works well, and now that Alice and Bob have identical keys Bob can use the same method to securely reply.

Meeting at a bar to exchange keys is inconvenient, though. It gets even more inconvenient when Alice and Bob are on opposite sides of an ocean.

Public-Key Encryption

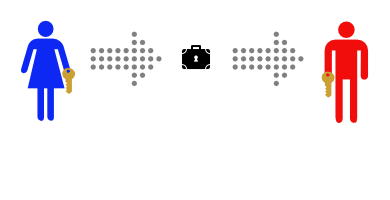

This time, Alice and Bob don’t ever need to meet. First Bob buys a padlock and matching key.

Then Bob mails the (unlocked) padlock to Alice, keeping the key safe.

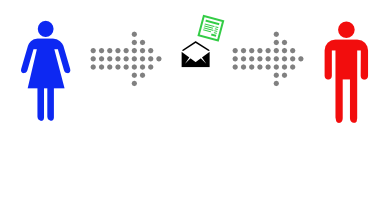

Alice buys a simple lockbox that closes with a padlock, and puts her message in it.

Then she locks it with Bob’s padlock, and mails it to Bob.

She knows that the mailman can’t read the message, as he has no way of opening the padlock. When Bob receives the lockbox he can open it with his key, and read the message.

This only works to send messages in one direction, but Alice could buy a blue padlock and key and mail the padlock to Bob so that he can reply.

Or, instead of sending a message in the padlock-secured lockbox, Alice could send Bob one of a pair of identical keys.

Then Alice and Bob can send messages back and forth in their symmetric-key lockbox, as they did in the first example.

This is how real world public-key encryption is often done.

Cryptography and Email

- steve

- Sep 16, 2014

A decade or so ago it was fairly rare for cryptography and email technology to intersect – there was S/MIME (which I’ve seen described as having “more implementations than users”) and PGP, which was mostly known for adding inscrutable blocks of text to mail and for some interesting political fallout, but not much else.

That’s changing, though. Authentication and privacy have been the focus of much of the development around email for the past few years, and cryptography, specifically public-key cryptography, is the tool of choice.

DKIM uses public-key cryptography to let the author (or their ESP, or anyone else) attach their identity to the message in a way that’s almost impossible to forge. That lets the recipient make informed decisions about whether to deliver the email or not.

DKIM relies on DNS to distribute it’s public keys, so if you can interfere with DNS, you can compromise DKIM. More than that, if you can compromise DNS you can break many security processes – interfering with DNS is an early part of many attacks. DNSSEC (Domain Name System Security Extensions) lets you be more confident that the results you get back from a DNS query are valid. It’s all based on public-key cryptography. It’s taken a long time to deploy, but is gaining steam.

TLS has escaped from the web, and is used in several places in email. For end users it protects their email (and their passwords) as they send mail via their smarthost or fetch it from their IMAP server. More recently, though, it’s begun to be used “opportunistically” to protect mail as it travels between servers – more than half of the mail gmail sees is protected in transit. Again, public-key cryptography. Perhaps you don’t care about the privacy of the mail you’re sending, but the recipient ISP may. Google already give better search ranking for web pages served over TLS – I wouldn’t be surprised if they started to give preferential treatment to email delivered via TLS.

The IETF is beginning to discuss end-to-end encryption of mail, to protect mail against interception and traffic analysis. I’m not sure exactly where it’s going to end up, but I’m sure the end product will be cobbled together using, yes, public-key cryptography. There are existing approaches that work, such as S/MIME and PGP, but they’re fairly user-hostile. Attempts to package them in a more user-friendly manner have mostly failed so far, sometimes spectacularly. (Hushmail sacrificed end-to-end security for user convenience, while Lavabit had similar problems and poor legal advice).

Not directly email-related, but after the flurry of ESP client account breaches a lot of people got very interested in two-factor authentication for their users. TOTP (Time-Based One-Time Passwords) – as implemented by SecureID and Google Authenticator, amongst many others – is the most commonly used method. It’s based on public-key cryptography. (And it’s reasonably easy to integrate into services you offer).

Lots of the other internet infrastructure you’re relying on (BGP, syn cookies, VPNs, IPsec, https, anything where the manual mentions “certificate” or “key” …) rely on cryptography to work reliably. Knowing a little about how cryptography works can help you understand all of this infrastructure and avoid problems with it. If you’re already a cryptography ninja none of this will be a surprise – but if you’re not, I’m going to try and explain some of the concepts tomorrow.

Useful bits of Cryptography – Hashes

- steve

- May 16, 2012

More than just PGP

Cryptography is the science of securing communication from adversaries. In the email world it’s most obvious use is tools like PGP or S/MIME that are used to encrypt a message so that it can only be read by the intended recipient, or to sign a message so that the recipient can be sure of who it came from. There are quite a few other aspects of sending email where a little cryptography is useful or essential, though – bounce management, suppression lists, unsubscription handling, DKIM and DMARC, amongst others.

Read MoreClicktracking link abuse

- steve

- Oct 11, 2010

If you use redirection links in the emails you send out, where a click on the link goes to your server – so you can record that someone clicked – before redirecting to the real destination, then you’ve probably already thought about how they can be abused.

Redirection links are simple in concept – you include a link that points to your webserver in email that you send out, then when recipients click on it they end up at your webserver. Instead of displaying a page, though, your webserver sends what’s called a “302 redirect” to send the recipients web browser on to the real destination. How does your webserver know where to redirect to? There are several different ways, with different tradeoffs: