Technical

Using Reply-To:

Yesterday I learned that some ESPs don’t support the reply to: address. I asked around to discover which ESPs did. Here’s what I learned.

Read MoreThe perfect email

More and more I’m moving away from consulting on technical setup issues as the solution to delivery problems. Delivery is not about the technical perfection of a message. Spammers get the technical right all the time. No, instead, delivery is about sending messages the user wants. While looking for something on the blog I found an old post from 2011 that’s still relevant today. In fact, I’d say it’s even more relevant today than it was when I wrote it 5 years ago.

Email is a fluid and ever changing landscape of things to do and not do.

Over the years my clients have frequently asked me to look at their technical setup and make sure that how they send mail complies with best practices. Previously, this was a good way to improve delivery. Spamware was pretty sloppy and blocking for somewhat minor technical problems was a great way to block a lot of spam.

More recently filter maintainers have been able to look at more than simple technical issues. They can identify how a recipient interacts with the mail. They can look at broad patterns, including scanning the webpages an email links to.

In short, email filters are very sophisticated and really do measure “wanted” versus “unwanted” down to the individual subscriber levels.

I will happily do technology audits for clients. But getting the technology right isn’t sufficient to get good delivery. What you really need to consider is: am I sending email that the recipient wants? You can absolutely get away with sloppy technology and have great inbox delivery as long as you are actually sending mail your recipients want to receive.

The perfect email is no longer measured in how perfectly correct the technology is. The perfect email is now measured by how perfect it is for the recipient.

May 2016: The Month in Email

Summer, already? Happy June! Here’s a look at our busy month of May.

I had a wonderful time in Atlanta at the Salesforce Connections 2016 conference, where I spoke on a panel about deliverability. While in Atlanta, I also visited our friends at Mailchimp, and later spoke at the Email Innovations conference in Las Vegas, where I did my best to avoid “explaining all the things”. Since my speaking schedule for 2017 is filling up already, I’m sure I’ll have plenty of opportunity to explain many more of the things over the next year or so. Let me know if there’s an event that might be a good fit for me, either as a keynote speaker or on a panel.

Steve contributed a few technical posts on the blog this month. He mentioned that Google has stopped supporting the obsolete SSLv3 and RC4, and he explored the ARC protocol, which is in development and review, and which will be useful in extending authentication through the email forwarding process.

Meri contributed to the blog this month as well, with a post on the Sanders campaign mailing list signup process. We’ve written about best practices for political campaigns before, and it’s always interesting to see what candidates are doing correctly and incorrectly with gathering addresses and reaching out to supporters.

In other best practices coverage, I pointed to some advice for marketers about authentication that I’d written up for the Only Influencers list, a really valuable community for email marketers. I wrote about purchased lists again (here’s a handy collection of all of my posts on the topic, just in case you need to convince a colleague that this isn’t a great idea). I also wrote about how getting the technical bits right isn’t always sufficient, which is also something I’ve written about previously. I also discussed the myth of using the word “free” in the subject line. As I said in the post, “Single words in the subject line don’t hurt your delivery, despite many, many, many blog posts out there saying they do. Filters just don’t work that way. They maybe, sorta, kinda used to, but we’ve gotten way past that now.”

On a personal note, I reminisced about the early days of mailing list culture and remembered a dear online friend as I explained some of why I care so much about email.

In my Ask Laura column, I covered CAN SPAM and transactional opt-outs. As always, if you have a general question about deliverability that I can answer in the column, please let me know.

Pete and Repeat

Pete and Repeat were on a boat. Pete fell out, who was left?

I was searching the blog for some resources today and these were the first two posts that showed up on the search results. I often feel like I’m repeating myself, but sometimes I am.

Check your tech

One of the things we do for just about every new client coming into WttW is have them send us an email from their bulk mail system. We then check it for technical correctness. This includes things like reviewing all the different From headers, rDNS of the connecting IP, List-Unsubscribe headers and authentication. This is always useful, IMO, because we often find things that were right when they were set up, but due to other changes at the customer they’re not 100% correct any more.

This happens to most of us. Even a company as small as Word to the Wise misses a rDNS update here or a hostname change update there when making infrastructure changes. That’s even when the same people know about email and are responsible for the infrastructure.

One of the most common problems we see is a SPF record that has accumulated include: files from previous providers. There are a couple reasons for this. One is the fact that SPF is set up while still at the old provider in anticipation of moving to the new provider. Once the move is made no one goes back to clean up the SPF record and remove the old entries. The other reason is that a lot of tech folks don’t like to delete things. Deleting things can lead to problems, and there’s no harm in a little extra in the SPF record. Except, eventually, there are so many include files that the lookup fails.

Every mailer should schedule a regular tech audit for their mail. Things change and sometimes in the midst of chance we don’t always catch some of the little details.

PTR Records

PTR records are easy to over look and they have a significant impact on your ability to deliver mail without them. Some ISP and mailbox providers will reject mail from IP addresses that do not have a PTR record created. PTR records are a type of DNS record that resolves an IP address to a fully qualified domain name or FQDN. The PTR records are also called Reverse DNS records. If you are sending mail on a shared IP address, you’ll want to check to make sure the PTR record is setup, however you most likely will not be able to change it. If you are on a dedicated IP address or using a hosting provider like Rackspace or Amazon AWS, you’ll want to create or change the PTR records to reflect your domain name.

We usually think about DNS records resolving a domain name such as www.wordtothewise.com to an IP address. A query for www.wordtothewise.com is sent to a DNS server and the server checks for a matching record and returns the IP address of 184.105.179.167. The A record for www is stored within the zone file for wordtothewise.com. PTR records are not stored within your domain zonefile, they are stored in a zonefile usually managed by your service provider or network provider.

Some service providers provide an interface where you can create the PTR record yourself, others require you to submit a support request to create or change the PTR record.

If you know what IP address you are sending mail from, use our web based DNS tool to check if you have a PTR record created.

http://tools.wordtothewise.com/dns

Checking for a PTR record for 184.105.179.167 returns167.128-25.179.105.184.in-addr.arpa 3600 PTR webprod.wordtothewise.com.

If you received Response: NXDOMAIN (There is no record of any type for x.x.x.x.in-addr.arpa), this means you’re missing the PTR record and need to create one ASAP if you are sending mail from that IP address!

AHBL Wildcards the Internet

AHBL (Abusive Host Blocking List) is a DNSBL (Domain Name Service Blacklist) that has been available since 2003 and is used by administrators to crowd-source spam sources, open proxies, and open relays. By collecting the data into a single list, an email system can check this blacklist to determine if a message should be accepted or rejected. AHBL is managed by The Summit Open Source Development Group and they have decided after 11 years they no longer wish to maintain the blacklist.

A DNSBL works like this, a mail server checks the sender’s IP address of every inbound email against a blacklist and the blacklist responses with either, yes that IP address is on the blacklist or no I did not find that IP address on the list. If an IP address is found on the list, the email administrator, based on the policies setup on their server, can take a number of actions such as rejecting the message, quarantining the message, or increasing the spam score of the email.

The administrators of AHBL have chosen to list the world as their shutdown strategy. The DNSBL now answers ‘yes’ to every query. The theory behind this strategy is that users of the list will discover that their mail is all being blocked and stop querying the list causing this. In principle, this should work. But in practice it really does not because many people querying lists are not doing it as part of a pass/fail delivery system. Many lists are queried as part of a scoring system.

Maintaining a DNSBL is a lot of work and after years of providing a valuable service, you are thanked with the difficulties with decommissioning the list. Popular DNSBLs like the AHBL list are used by thousands of administrators and it is a tough task to get them to all stop using the list. RFC6471 has a number of recommendations such as increasing the delay in how long it takes to respond to a query but this does not stop people from using the list. You could change the page responding to the site to advise people the list is no longer valid, but unlike when you surf the web and come across a 404 page, a computer does not mind checking the same 404 page over and over.

Many mailservers, particularly those only serving a small number of users, are running spam filters in fire-and-forget mode, unmaintained, unmonitored, and seldom upgraded until the hardware they are running on dies and is replaced. Unless they do proper liveness detection on the blacklists they are using (and they basically never do) they will keep querying a list forever, unless it breaks something so spectacularly that the admin notices it.

So spread the word,

M3AAWG Recommends TLS

SSL or Secure Sockets Layer is protocol designed to provide a secure way of transmitting information between computer systems. Originally created by Netscape and released publicly as SSLv2 in 1995 and updated to SSLv3 in 1996. TLS or Transport Layer Security was created in 1999 as a replacement for SSLv3. TLS and SSL are most commonly used to create a secure (encrypted) connection between your web browser and websites so that you can transmit sensitive information like login credentials, passwords, and credit card numbers.

M3AAWG published a initial recommendation that urges the disabling of all versions of SSL. It has been a rough year for encryption security, first with Heartbleed vulnerability with the OpenSSL library, and again with POODLE which stands for “Padding Oracle on Downgraded Legacy Encryption” that was discovered by Google security researchers in October of 2014. On December 8, 2014 it was reported that TLS implementations are also vulnerable to POODLE attack, however unlike SSLv3, TLS can be patched where as SSL 3.0 has a fundamental issue with the protocol.

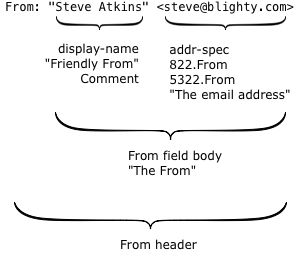

The anatomy of From:

Compared with some of the more complex pieces of the email protocol the From: header seems deceptively simple. But I’ve heard several people be confused about what it’s made up of over the past couple of months, so I thought I’d dig a bit deeper into how it’s defined and how it’s used in practice.

Here’s a simple example:

There are two interesting parts.

The first is what’s technically called the display-name, but more commonly known as the “friendly from” in the bulk email industry. It has no meaning within the email protocol, it’s just text that’s displayed to the recipient to describe who an email was sent by. Because it’s just text, you can put anything you like in there, but it’s usually either the name of the person who wrote the mail or the name of the company or brand that sent it.

The second is the actual email address, the thing with an at-sign in it. Surprisingly, this isn’t used at all during the actual delivery of the email; there’s a hidden field (called the return path or the 5321.MailFrom or the envelope sender or the bounce address) that’s used instead. For person-to-person email it’s usually the same address, but for bulk mail it’s often different.

So what does the actual email address, the 5322.From, mean? For that we go to the document that specifies what email headers mean – RFC 5322, “Internet Message Format”. (RFC 5322 is the updated replacement of the older RFC 822 – and that’s why the actual email address is often called the 822.From or 5322.From when people are being precise about exactly which email address they’re talking about).

RFC 5322 says “The From: field specifies the author of the message, that is, the mailbox of the person or system responsible for the writing of the message.” and “In all cases, the From: field SHOULD NOT contain any mailbox that does not belong to the author of the message”. It’s the email address of the author of the message.

(In some cases the email may have been written by the author, but then sent on their behalf by someone else. RFC 5322 says that in that situation the email address in the From field is still the author of the message. The person who sent the message gets their own field, “Sender:”).

What is the 5322.From used for? During the delivery process it’s used for some sorts of filtering and authentication. In particular, if you’re reading about DMARC you’ll see “identifier alignment” mentioned a lot – which basically means “the only domain we care about authenticating is the one in the 5322.From”. It’s also the usual field that’s used in user-visible mail filtering such as whitelisting email addresses that are in the users address book.

In the mail client itself the most obvious use of the 5322.From is that when you hit reply, that’s the email address your reply will go to by default. The author of the mail can override that by adding a Reply-To field, containing one or more email addresses if they want different behaviour. It’s also commonly used to filter email and to group mails by author.

What’s displayed to the end user? Originally the entire content of the From: header was shown in the recipients mailbox but it’s now fairly common to display just the friendly from, with no mention of the email address at all. That started in mobile clients, where space is at a premium and the friendly from is just, well, friendlier – but it’s spread to desktop and webmail clients too. In Yahoo webmail the 5322.From isn’t displayed anywhere at all unless you find the View Full Header menu option and dig through the raw headers, and my phone doesn’t display it anywhere obvious and only recently made it possible to see it at all.

Horses, not zebras

I was first introduced to the maxim “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras” when I worked in my first molecular biology lab 20-some-odd years ago. I’m no longer a gene jockey, but I still find myself applying this to troubleshooting delivery problems for clients.

It’s not that I think all delivery problems are caused by “horses”, or that “zebras” never cause problems for email delivery. It’s more that there are some very common causes of delivery problems and it’s a more effective use of time to address those common problems before getting into the less common cases.

This was actually something that one of the mailbox provider reps said at M3AAWG in SF last month. They have no problem with personal escalations when there’s something unusual going on. But, the majority of issues can be handled through the standard channels.

What are the horses I look for with delivery problems.

Ad-hoc analysis

I often pull emails into a database to analyze them, but sometimes I want something simpler. Emails are typically stored in one of two ways: mbox format, where an entire mailbox is stored in a single file, and maildir format, where a mailbox is a directory with one file in it for each email.

My desktop mail application is Mail.app on OS X, and it stores messages in a maildir-ish format, so I’m going to work with that here. If you’re using mbox format mailboxes it’s a little trickier (but you can use a tool called formmail to split an mbox style format into a maildir directory and go from there).

I want to gather some statistics on mail I’ve sent to abuse desks, so the first thing I do is open up a terminal window and change directory to where my “Sent Messages” mailbox is:cd Library/Mail/V2/IMAP-steve@misc.wordtothewise.com/Sent Messages.mbox

(Tab completion is really useful for navigating through the mailbox hierarchy.)

Then I need to go through every email (file) in that directory, for each file find the “To:” header and check to see if it was sent to an abuse desk. If it was sent to an abuse desk I want to find the email address for each one, count how many times I see that email address and find the top twenty or so abuse desks I send reports to. I can do all that with a single command line:find . -type f -exec egrep -m1 '^To:' {} ; | egrep -o 'abuse@[a-zA-Z0-9._-]+' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head -20

(Enter that all as a single line, even though it’s wrapped into two here).

That’s a bit much to understand all at once, so lets redo that in several stages, with an intermediate file so we can see what’s going on.find . -type f -exec egrep -m1 '^To:' {} ; >tolines.txt

The find command finds all the files in a directory and does something with them. In this case we start looking in the current directory (“.”), look just for files (“-type f”) and for each file we find we run that file through another command (“-exec egrep -m1 ‘^To:’ {} ;”) and write the result of that command to a file (“>tolines.txt”). The egrep command we run for each file goes through the file and prints out the first (“-m1”) line it finds that begins with “To:” (“‘^To:'”). If you run that and take a look at the file it creates you can see one line for each message, containing the “To:” header (or at least the first line of it).

The next thing to do is to go through that and pull out just the email addresses – and just the ones that are sent to abuse desks:egrep -o 'abuse@[a-zA-Z0-9._-]+' tolines.txt

This uses egrep a second time, this time to look for lines that look like an email address (“‘abuse@[a-zA-Z0-9._-]+'”) and when it finds one print out just the part of the line that matched the pattern (“-o”).

Running that gives us one line of output for each email we’re interested in, containing the address it was sent to. Next we want to count how many times we see each one. There’s a command line idiom for that:egrep -o 'abuse@[a-zA-Z0-9._-]+' tolines.txt | sort | uniq -c

This takes all the lines and sorts (“sort”, reasonably enough) them – so that identical lines will be next to each other – then counts runs of identical lines (“uniq -c”). We’re nearly there – the result of this is a count and an email address on each line. We just need to find the top 20:egrep -o 'abuse@[a-zA-Z0-9._-]+' tolines.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head -20

Each line begins with the count, so we can use sort again, this time telling it to sort by number, high to low (“sort -nr”). Finally, “head -20” will print just the first 20 lines of the result.

The final result is this:

Weird mail problems today? Clear your DNS cache!

A number of sources are reporting this morning that there was a problem with some domains in the .com zone yesterday. These problems caused the DNS records of these domains to become corrupted. The records are now fixed. Some of the domains, however, had long TTLs. If a recursive resolver pulled the corrupted records, it could take up to 2 days for the new records to naturally age out.

Folks can fix this by flushing their DNS cache, thus forcing the recursive resolver to pull the uncorrupted records.

EDIT: Cisco has published some more information about the problem. ‘Hijacking’ of DNS Records from Network Solutions

Post-mortem on the Spamhaus DOS

There’s been a ton of press over the last week on the denial of service attack on Spamhaus. A lot of it has been overly excited and exaggerated, probably in an effort to generate clicks and ad revenue at the relevant websites. But we’re starting to see the security and network experts talk about the attack, it’s effects and what it tells us about future attacks.

I posted an analysis from the ISC yesterday. They had some useful information about the attack and about what everyone should be doing to stop from contributing to future attacks (close your open DNS resolver). The nice thing about this article is that it looked at the attack from the point of view of network health and security.

Today another article was published in TechWeekEurope that said many of the same things that the ISC article did about the size and impact of the attacks.

What’s the takeaway from this?

More on the attack against Spamhaus and how you can help

While much of the attack against Spamhaus has been mitigated and their services and websites are currently up, the attack is still ongoing. This is the biggest denial of service attack in history, with as much as 300 gigabits per second hitting Spamhaus servers and their upstream links.

This traffic is so massive, that it’s actually affecting the Internet and web surfers in some parts of the world are seeing network slowdown because of this.

While I know that some of you may be cheering at the idea that Spamhaus is “paying” for their actions, this does not put you on the side of the good. Spamhaus’ actions are legal. The actions of the attackers are clearly illegal. Not only is the attack itself illegal, but many of the sites hosted by the purported source of the attacks provide criminal services.

By cheering for and supporting the attackers, you are supporting criminals.

Anyone who thinks that an appropriate response to a Spamhaus listing is an attack on the very structure of the Internet is one of the bad guys.

You can help, though. This attack is due to open DNS resolvers which are reflecting and amplifying traffic from the attackers. Talk to your IT group. Make sure your resolvers aren’t open and if they are, get them closed. The Open Resolver Project published its list of open resolvers in an effort to shut them down.

Here are some resources for the technical folks.

Open Resolver Project

Closing your resolver by Team Cymru

BCP 38 from the IETF

Ratelimiting DNS

News Articles (some linked above, some coming out after I posted this)

NY Times

BBC News

Cloudflare update

Spamhaus dDOS grows to Internet Threatening Size

Cyber-attack on Spamhaus slows down the internet

Cyberattack on anti-spam group Spamhaus has ripple effects

Biggest DDoS Attack Ever Hits Internet

Spamhaus accuses Cyberbunker of massive cyberattack

You can't technical yourself out of delivery problems

In many cases these days, many more cases than a lot of senders want to admit, delivery problems at the big ISPs are a result of sending mail recipients just don’t care about. The reason your mail is going to bulk? It’s not because you have minor problems in your headers. It’s not because you have some formatting issues. The reason is because your recipients just don’t care if the ISP delivers your mail or not.

A few years ago the bulk of my clients hired me to do technical audits for their mail. I fixed a lot of delivery problems that way. They’d send me their email and I’d run it through tools here and identify things they were doing that were likely to be causing problems. I’d give them some suggestions of things to change. Believe it or not, minor tweaks to headers and configuration actually did make a lot of difference in delivery.

Over time, though those tweaks less effective to fix delivery problems. Some of it is due to the MTA vendors, they’re a lot better at sending technically correct mail than they were before. There are also a lot more people giving good advice on the underlying structure and format of emails so senders can send technically clean email. I started seeing technically perfect emails from clients who were seeing major delivery problems.

There are a number of reasons that technical fixes don’t work like they used to. The short version, though, is that ISPs have dealt with much of the really blatant spam and they can focus more time and energy on the “grey mail”.

This makes my job a little harder. I can no longer just look at an email, maybe run it through some of our tools and provide a few suggestions that fix delivery problems. Delivery isn’t that simple any longer. Filters are really more focused on how the recipients react to mail. That means I need to know a lot more about a clients email program before I can even start to identify what might be causing the delivery issues.

I wish it were still so simple I could give minor technical tweaks that would appear to magically improve a client’s delivery. It was a lot simpler process then. But filters have evolved, and senders must evolve, too.

The Physics of the Email Universe

We talk a lot about rules and best practices in email, but we’re mostly talking about “squishy” rules-of-thumb that are based on simplified models of how mail systems, spam filters, recipients, postmasters and blacklist operators behave. They’re the biology, ecology and sociology of the email ecosystem.

There’s another set of rules we tend to only mention in passing, if at all, though. They’re the steely, sharp-edged laws that control the email universe. They’re the RFCs that define how email works and make sure that mail systems written by hundreds of different people across the globe all work and all interoperate with each other.

Building a message from Zeros and Ones

RFC 5322 – Internet Message Format

This tells you everything you need to know about crafting a simple email, with a subject line, a sender, some recipients and a simple plain-text message. It’s also the foundation of all fancier emails. If you’re creating emails, this is where to start.

A little more than plain ASCII

RFC 2047 – MIME Part 3: Message Header Extensions for Non-ASCII Text

RFC 2047 is one small part of the MIME (Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions) suite of protocols that allow you to include pictures and attachments and prettily formatted text and comic sans in your email. This part defines how you can put things other than the plainest of plain text in your subject lines or in the “friendly from” of your message. It’s what allows you to put Hiragana, or Cyrillic, or umlauts, or cedillas, or properly matched double quotes in your subject line. It also let’s you put hearts or smiley faces or other little pictograms there – but nothing this useful is going to be perfect.

RFC 2045 – MIME Part 1: Format of Internet Message Bodies

This shows how to send an image, or a plain text mail in a different character set, or an HTML mail. It doesn’t tell you how to send plain text and HTML, or to send HTML with embedded images, or a message with an attached document. For that you need…

Finally, Modern Email

RFC 2046 – MIME Part 2: Media Types

This builds on RFC 2045 to allow you to have many different chunks in a message – this is what you need if you want to send “proper” HTML mail with a plain text alternative, or if you want embedded images or attachments.

Getting From A To B

RFC 5321 – Simple Mail Transfer Protocol

A message isn’t much use unless you send it somewhere. RFC 5321 explains the mysteries of actually sending that message over the wire to the recipient. If you need to know about the different phases of a message delivery, what “4xx” and “5xx” actually mean, why there’s not really any such thing as a hard or soft bounce defined, just temporary or permanent failures, or anything else about actually sending mail or diagnosing mail delivery, this is your starting point.

The Rest Of The Iceberg

I’ve only touched on the very smallest tip of the email iceberg here. There’s much, much more – both in RFCs and ad-hoc non-RFC standards. If you’re interested in more, this is a decent place to start.

Who leaked my address, and when?

Providing tagged email addresses to vendors is fascinating, and at the same time disturbing. It lets me track what a particular email address is used for, but also to see where and when they’ve leaked to spammers.

I’d really like to know who leaked an email address, and when.

All my inbound mail is sorted into “spam” and “not-spam” by a combination of SpamAssassin, some static sieve rules and a learning spam filter in my mail client. That makes it fairly easy for me to look at my “recent spam”. That’s a huge amount of data, though, something like 40,000 pieces of spam a month.

Finding the needle of interesting data in that haystack is going to take some automation. As I’ve mentioned before you can do quite a lot of useful work with a mix of some little perl scripts and some commandline tools.

I’m interested in the first time a tagged address started receiving spam, so I start off with a perl script that will take a directory full of emails, one per file, find the ones that were sent to a tagged address and print out that address and the time I received the email. I can’t rely on the Date: header, as that’s under the control of the spammer, and often bogus. But I can rely on the timestamp my server adds when it receives the email – and it records that in the first Received: header in the message.

Analysing a data breach – CheetahMail

I often find myself having to analyze volumes of email, looking for common factors, source addresses, URLs and so on as part of some “forensics” work, analyzing leaked emails or received spam for use as evidence in a case.

For large volumes of mail where I might want to dig down in a lot of detail or generate graphical or statistical reports I tend to use Abacus to slurp in and analyze all the emails, store them in a SQL database in an easy to handle format and then do the ad-hoc work from a SQL commandline. For smaller work, though, you can get a long way with unix commandline tools and some basic perl scripting.

This morning I received Ukrainian bride spam to a tagged address that I’d only given to one vendor, RedEnvelope, so that address has leaked to criminal spammers from somewhere. Looking at a couple of RedEnvelope’s emails I see they’re sending from a number of sources, so I decided to dig a little deeper.

I started by searching for all emails to that tagged address in my mail client, then copied all the matching emails to a newly created folder. Then I took a copy of that folder and split it into one file per email using a shell one-liner:

Character encoding

This morning, someone asked an interesting question.

Last time I worked with the actual HTML design of emails (a long time ago), <head> was not really needed. Is this still true for the most part? Any reason why you still want to include <head> + meta, title tags in emails nowadays?

Read More

Defending against the hackers of 1995

Passwords are convenient for the end user, but it’s too easy to lose control of them. People share them with other people. People write them down, where they can be read. People send them in email, and that email is easily intercepted. People’s web browsers store the passwords, so they can log in automatically. Worst of all, perhaps, people tend to use the same username and password at many different websites. If just one of those websites is compromised (or even run as a password collecting scam) then those passwords can be used to attack accounts at all of the others.

Two factor authentication that uses an uncopyable physical device (such as a cellphone or a security token) as a second factor mitigates most of these threats very effectively. Weaker two factor authentication using digital certificates is a little easier to misuse (as the user can share the certificate with others, or have it copied without them noticing) but still a lot better than a password.

Security problems solved, then?

What is Two Factor Authentication?

Two factor authentication, or the snappy acronym 2FA, is something that you’re going to be hearing a lot about over the next year or so, both for use by ESP employees (in an attempt to reduce the risks of data theft) and by ESP customers (attempting to reduce the chance of an account being misused to send spam).  What is Authentication?

What is Authentication?

In computer security terms authentication is proving who you are – when you enter a username and a password to access your email account you’re authenticating yourself to the system using a password that only you know.

Authentication (“who you are”) is the most visible part of computer access control, but it’s usually combined with two other A’s – authorization (“what you are allowed to do”) and accounting (“who did what”) to form an access control system.

And what are the two factors?

Two factor authentication means using two independent sources of evidence to demonstrate who you are. The idea behind it is that it means an attacker need to steal two quite different bits of information, with different weaknesses and attack vectors, in order to gain access. This makes the attack scenario much more complex and difficult for an attacker to carry out.

It’s important that the different factors are independent – requiring two passwords doesn’t count as 2FA, as an attack that can get the first password can just as easily get the second password. Generally 2FA requires the user to demonstrate their identity via two out of three broad ways:

Real. Or. Phish?

After Epsilon lost a bunch of customer lists last week, I’ve been keeping an eye open to see if any of the vendors I work with had any of my email addresses stolen – not least because it’ll be interesting to see where this data ends up.

Yesterday I got mail from Marriott, telling me that “unauthorized third party gained access to a number of Epsilon’s accounts including Marriott’s email list.”. Great! Lets start looking for spam to my Marriott tagged address, or for phishing targeted at Marriott customers.

I hit what looks like paydirt this morning. Plausible looking mail with Marriott branding, nothing specific to me other than name and (tagged) email address.

It’s time to play Real. Or. Phish?

1. Branding and spelling is all good. It’s using decent stock photos, and what looks like a real Marriott logo.

All very easy to fake, but if it’s a phish it’s pretty well done. Then again, phishes often steal real content and just change out the links.

Conclusion? Real. Maybe.

2. The mail wasn’t sent from marriott.com, or any domain related to it. Instead, it came from “Marriott@marriott-email.com”.

This is classic phish behaviour – using a lookalike domain such as “paypal-billing.com” or “aolsecurity.com” so as to look as though you’re associated with a company, yet to be able to use a domain name you have full control of, so as to be able to host websites, receive email, sign with DKIM, all that sort of thing.

Conclusion? Phish.

3. SPF pass

Given that the mail was sent “from” marriott-email.com, and not from marriott.com, this is pretty meaningless. But it did pass an SPF check.

Conclusion? Neutral.

4. DKIM fail

Authentication-Results: m.wordtothewise.com; dkim=fail (verification failed; insecure key) header.i=@marriott-email.com;

As the mail was sent “from” marriott-email.com it should have been possible for the owner of that domain (presumably the phisher) to sign it with DKIM. That they didn’t isn’t a good sign at all.

Conclusion? Phish.

5. Badly obfuscated headers

From: =?iso-8859-1?B?TWFycmlvdHQgUmV3YXJkcw==?= <Marriott@marriott-email.com>

Subject: =?iso-8859-1?B?WW91ciBBY2NvdW50IJYgVXAgdG8gJDEwMCBjb3Vwb24=?=

Base 64 encoding of headers is an old spammer trick used to make them more difficult for naive spam filters to handle. That doesn’t work well with more modern spam filters, but spammers and phishers still tend to do it so as to make it harder for abuse desks to read the content of phishes forwarded to them with complaints. There’s no legitimate reason to encode plain ascii fields in this way. Spamassassin didn’t like the message because of this.

Conclusion? Phish.

6. Well-crafted multipart/alternative mail, with valid, well-encoded (quoted-printable) plain text and html parts

Just like the branding and spelling, this is very well done for a phish. But again, it’s commonly something that’s stolen from legitimate email and modified slightly.

Conclusion? Real, probably.

7. Typical content links in the email

Most of the content links in the email are to things like “http://marriott-email.com/16433acf1layfousiaey2oniaaaaaalfqkc4qmz76deyaaaaa”, which is consistent with the from address, at least. This isn’t the sort of URL a real company website tends to use, but it’s not that unusual for click tracking software to do something like this.

Conclusion? Neutral

8. Atypical content links in the email

We also have other links:

Multipart MIME cheat sheet

I’ve had a couple of people ask me about MIME structure recently, especially how you create multipart messages, when you should use them and which variant of multipart you use for different things. (And I’m working on a MIME parser / generator for Abacus at the moment, so it’s all fresh in my mind)

So I’ve put together a quick cheat sheet, showing the structure of four common types of email, and how their MIME structure looks.

Yes, we have no IP addresses, we have no addresses today

We’ve just about run out of the Internet equivalent of a natural resource – IP addresses.

Read MoreClicktracking 2: Electric Boogaloo

A week or so back I talked about clicktracking links, and how to put them together to avoid abuse and blocking issues.

Since then I’ve come across another issue with click tracking links that’s not terribly obvious, and that you’re not that likely to come across, but if you do get hit by it could be very painful – phishing and malware filters in web browsers.

First, some background about how a lot of malware is distributed, what’s known as “drive-by malware”. This is where the hostile code infects the victims machine without them taking any action to download and run it, rather they just visit a hostile website and that website silently infects their computer.

The malware authors get people to visit the hostile website in quite a few different ways – email spam, blog comment spam, web forum spam, banner ads purchased on legitimate websites and compromised legitimate websites, amongst others.

That last one, compromised legitimate websites, is the type we’re interested in. The sites compromised aren’t usually a single, high-profile website. Rather, they tend to be a whole bunch of websites that are running some vulnerable web application – if there’s a security flaw in, for example, WordPress blog software then a malware author can compromise thousands of little blog sites, and embed malware code in each of them. Anyone visiting any of those sites risks being infected, and becoming part of a botnet.

Because the vulnerable websites are all compromised mechanically in the same way, the URLs of the infected pages tend to look much the same, just with different hostnames – http://example.com/foo/bar/baz.html, http://www.somewhereelse.invalid/foo/bar/baz.html and http://a.net/foo/bar/baz.html – and they serve up just the same malware (or, just as often, redirect the user to a site in russia or china that serves up the malware that infects their machine).

A malware filter operator might receive a report about http://example.com/foo/bar/baz.html and decide that it was infected with malware, adding example.com to a blacklist. A smart filter operator might decide that this might be just one example of a widespread compromise, and go looking for the same malware elsewhere. If it goes to http//a.net/foo/bar/baz.html and finds the exact same content, it’ll know that that’s another instance of the infection, and add a.net to the blacklist.

What does this have to do with clickthrough links?

Well, an obvious way to implement clickthrough links is to use a custom hostname for each customer (“click.customer.com“), and have all those pointing at a single clickthrough webserver. It’s tedious to setup the webserver to respond to each hostname as you add a new customer, though, so you decide to have the webserver ignore the hostname. That’ll work fine – if you have customer1 using a clickthrough link like http://click.customer1.com/123/456/789.html you’d have the webserver ignore “click.customer1.com” and just read the information it needs from “123/456/789.html” and send the redirect.

But that means that if you also have customer2, using the hostname click.customer2.com, then the URL http://click.customer2.com/123/456/789.html it will redirect to customer1’s content.

If a malware filter decides that http://click.customer1.com/123/456/789.html redirects to a phishing site or a malware download – either due to a false report, or due to the customers page actually being infected – then they’ll add click.customer1.com to their blacklist, meaning no http://click.customer1.com/ URLs will work. So far, this isn’t a big problem.

But if they then go and check http://click.customer2.com/123/456/789.html and find the same redirect, they’ll blacklist click.customer2.com, and so on for all the clickthrough hostnames of yours they know about. That’ll cause any click on any URL in any email a lot of your customers send out to go to a “This site may harm your computer!” warning – which will end up a nightmare even if you spot the problem and get the filter operators to remove all those hostnames from the blacklist within a few hours or a day.

Don’t let this happen to you. Make sure your clickthrough webserver pays attention to the hostname as well as the path of the URL.

Use different hostnames for different customers clickthrough links. And if you pick a link from mail sent by Customer A, and change the hostname of that link to the clickthrough hostname of Customer B, then that link should fail with an error rather than displaying Customer A’s content.

Clicktracking link abuse

If you use redirection links in the emails you send out, where a click on the link goes to your server – so you can record that someone clicked – before redirecting to the real destination, then you’ve probably already thought about how they can be abused.

Redirection links are simple in concept – you include a link that points to your webserver in email that you send out, then when recipients click on it they end up at your webserver. Instead of displaying a page, though, your webserver sends what’s called a “302 redirect” to send the recipients web browser on to the real destination. How does your webserver know where to redirect to? There are several different ways, with different tradeoffs:

Abuse Reporting Format

J.D. has a great post digging into ARF, the abuse reporting format used by most feedback loops.

If you’re interested in following along, you might find this annotated example ARF report handy.

Poor delivery can't be fixed with technical perfection

There are a number of different things delivery experts can do help senders improve their own delivery. Yes, I said it: senders are responsible for their delivery. ESPs, delivery consultants and deliverability experts can’t fix delivery for senders, they can only advise.

In my own work with clients, I usually start with making sure all the technical issues are correct. As almost all spam filtering is score based, and the minor scores given to things like broken authentication and header issues and formatting issues can make the difference between an email that lands in the inbox and one that doesn’t get delivered.

I don’t think I’m alone in this approach, as many of my clients come to me for help with their technical settings. In some cases, though, fixing the technical problems doesn’t fix the delivery issues. No matter how much my clients tweak their settings and attempt to avoid spamfilters by avoiding FREE!! in the subject line, or changing the background, they still can’t get mail in the inbox.

Why not? Because they’re sending mail that the recipients don’t really want, for whatever reason. There are so many ways a sender can collect an email address without actually collecting consent to send mail to that recipient. Many of the “list building” strategies mentioned by a number of experts involve getting a fig leaf of permission from recipients without actually having the recipient agree to receive mail.

Is there really any difference in permission between purchasing a list of “qualified leads” and automatically adding anyone who makes a purchase at a website to marketing lists? From the recipient’s perspective they’re still getting mail they don’t want, and all the technical perfection in the world can’t overcome the negative reputation associated with spamming.

The secret to inbox delivery: don’t send mail that looks like spam. That includes not sending mail to people who have not expressly consented to receive mail.

The view from a blacklist operator

We run top-level DNS servers for several blacklists including the CBL, the blacklist of infected machines that the SpamHaus XBL is based on. We don’t run the CBL blacklist itself (so we aren’t the right people to contact about a CBL listing) we just run some of the DNS servers – but that means that we do get to see how many different ways people mess up their spam filter configurations.

This is what a valid CBL query looks like:

How to disable a domain

Sometimes you might want to make it clear that a domain isn’t valid for email.

Perhaps it’s a domain or subdomain that’s just used for infrastructure, perhaps it’s a brand-specific domain you’re only using for a website. Or perhaps you’re a target for phishing and you’ve acquired some lookalike domains, either pre-emptively or after enforcement action against a phisher, and you want to make clear that the domain isn’t legitimate for email.

There are several things to check before disabling email.

1. Are you receiving email at the domain? Is anyone else?

Check the MX records for the domain, using “host -t mx example.com” from a unix commandline, or using an online DNS tool such as xnnd.com.

If they’re pointing at a mailserver you control, check to see where that mail goes. Has anything been sent there recently?

If they’re pointing at a mailserver that isn’t yours, try and find out why.

If there are no MX records, but there is an A record for the domain then mail will be delivered there instead. Check whether that machine receives email for the domain and, if so, what it does with it.

Try sending mail to postmaster@ the domain, for instance postmaster@example.com. If you don’t get a bounce within a few minutes then that mail may be being delivered somewhere.

2. Are you sending email from the domain? Is anyone else?

You’re more likely to know whether you’re sending mail using the domain, but there’s a special case that many people forget. If there’s a server that has as it’s hostname the domain you’re trying to shut down then any system software running no that server – monitoring software, security alerts, output from cron and so on – is probably using that hostname to send mail. If so, fix that before you go any further.

3. Will you need mail sent to that domain for retrieving passwords?

If there are any services that might have been set up using an email address at the domain then you might need a working email address there to retrieve lost passwords. Having to set email back up for the domain in the future to recover a password is time consuming and annoying.

The domain registration for the domain itself is a common case, but if there’s any dns or web hosting being used for the domain, check the contact information being used there.

4. How will people contact you about the domain?

Even if you’re not using the domain for email it’s quite possible that someone may need to contact you about the domain, and odds are good they’ll want to use email. Make sure that the domain registration includes valid contact information that identifies you as the owner and allows people to contact you easily.

If you’re hosting web content using the domain, make sure there’s some way to contact you listed there. If you’re not, consider putting a minimal webpage there explaining the ownership, with a link to your main corporate website.

5. Disabling email

The easiest way to disable email for a domain is to add three DNS records for the domain. In bind format, they look like:

The secret to fixing delivery problems

There is a persistent belief among some senders that the technical part of sending email is the most important part of delivery. They think that by tweaking things around the edges, like changing their rate limiting and refining bounce handling, their email will magically end up in the inbox.

This is a gross misunderstanding of the reasons for bulk foldering and blocking by the ISPs. Yes, technical behaviour does count and senders will find it harder to deliver mail if they are doing something grossly wrong. In my experience, though, most technical issues are not sufficient to cause major delivery problems.

On the other hand, senders can do everything technically perfect, from rate limiting to bounce handling to handling feedback loops through authentication and offer wording and still have delivery problems. Why? Sending unwanted mail trumps technical perfection. If no one wants the email mail then there will be delivery problems.

Now, I’ve certainly dealt with clients who had some minor engagement issues and the bulk of their delivery problems were technical in nature. Fix the technical problems and make some adjustments to the email and mail gets to the inbox. But with senders who are sending unwanted email the only way to fix delivery problems is to figure out what recipients want and then send mail meeting those needs.

Persistent delivery problems cannot be fixed by tweaking technical settings.

Analysing lead-gen spam

Yesterday I showed how major companies hire hard core spammers.

Today I’m going to show you some of the technical details as to how I found that data. This is a fairly quick and shallow analysis, the sort of thing I’d typically do for a client to help them decide whether the case was worth pursuing before expending too much money and time on investigation and legal paperwork. I’ve also done it using standard command line tools that are available on pretty much any unix command line (and windows, with a little effort).

There are several questions to answer about the email in question.

Which is better UTF-8 or ISO-?

Someone asked today on a mailing list whether they should be using UTF-8 or “ISO” encoding for sending email. What’s the best choice depends on some of the details of the situation, but here’s the answer I gave:

UTF-8 will work for pretty much anything, as it’s just an 8 bit encoding scheme for Unicode (which is supposed to be the one character encoding to rule them all). It’s well supported in most languages and development environments – Windows has been native UTF-16 under the covers since the mid 90s, for instance – and typical messages that use mainstream glyphs should render well from utf-8 in most western MUAs and browsers.

There are still a very few old or broken clients out there that will not handle UTF-8 well but (outside the asian language market, where there’s still some non-ASCII, non-Unicode legacy usage) they’re typically ones that don’t really handle any character set encoding well and the only thing safe to send to them is either plain ASCII or whichever ASCII superset their OS happens to support natively (which is probably an argument for sending Windows-1252 codepage, but not a terribly strong one).

The various extended ASCIIs (such as ISO-8859-*) will only work for messages that are written solely using characters from that character set. If you have even one character in a message that cannot be expressed in ISO-8859-1, then you can’t use ISO-8859-1 to send that message.

ISO-8859-1 (aka Latin1) is fairly sloppy in some respects – it has no apostrophe, nor single quotes, for instance – but it can handle an awful lot of languages, from Kurdish to Swahili. It can’t handle Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, Hungarian and Welsh particularly well, nor can it show the Euro symbol (ISO-8859-14 or -15 are needed for some characters there).

A common problem is that many people (and the software they write) think that Windows uses Latin1. It doesn’t, it uses Windows-1252. If you accept messages written on Windows, using the Windows-1252 code page, and throw them out on the wire as ISO-8859-1 what you end up with is not quite right. It mostly works, as the two codepages overlap quite a bit, but they have different glyphs in the 0x80-0x9f range. So if you use single or double quotes (“smart quotes”), or the Euro symbol, or ellipses, or bullet, or the trademark symbol in your message they’ll be garbled. This is so common that some mail clients and web browsers will actually treat a document that claims to be ISO-8859-1 as Windows-1252, but that’s a bug workaround and not something it’s really safe to rely on.

If you’re doing personalized messages, and you’re sending one of them to Győző and one of them to Eiður then you may have to use different character sets for the two messages. If you’re talking about Győző and personalizing it for Eiður then you might find things break horribly.

Someone probably has some concrete data on mail client character set support, broken down by region and language, but my understanding is that this is a reasonable approach:

Troubleshooting the simple stuff

I was talking with one of my Barry pals recently and was treated to a rant regarding deliverability experts that can’t manage simple things. We’ve been having an ongoing conversation recently about the utterly stupid and annoying questions some senders ask. Last week, I was ranting about a delivery person asking what “5.7.1. Too many receipts this session” meant. This morning I got an IM.

Read MoreEmail is store and forward

Many of us are so used to email appearing instantaneous, we forget that the underlying protocol was never designed for instant messaging. When the SMTP protocol was originally proposed it was designed to support servers that may have had intermittent connectivity. The protocol allowed for email to be spooled to disk and then sent when resources were available. In fact, almost everyone who was around more than 10 years ago knows of a case where an email took weeks, months or even years to deliver.

These days we’re spoiled. We expect the email we send to friends and relatives to show up in their mailbox within moments of sending it. We expect that sales receipt or e-ticket to show up in our mailbox within instants of a purchase. We expect that our ISPs will get us email immediately, if not sooner.

But there are a lot of things that can slow down email delivery. At several points in the process an email may be spooled to disk. It stays on the spool until the next part of the delivery process can happen. Other points of slowdown include the various anti-spam, anti-virus and anti-phishing protections that ISPs must implement. Then add in the extreme volume of email (around 10 billion messages a day) and all of a sudden email delivery is slower than many senders and recipients expect it to be. This delay is not ideal, but the system is designed so that mail is not silently discarded.

While individual emails may be delayed, most users will rarely see that delay in the email that they send. Bulk senders, who may be sending thousands or hundreds of thousands of emails a day, may see more delays in a single send than the average user sees in years of sending one-to-one email.

Email is store and forward, not instant. Sometimes that means there is a delay in getting email into the recipients inbox. And, sometimes there isn’t anything anyone can do to speed up delivery, except to adjust expectations of how email works.

What is an email address? (part two)

Yesterday I talked about the technical definitions of an email address. Eventually on Monday I’m going to talk about some useful day-to-day rules about email address acquisition and analysis, but first I’m going to take a detour into tagging or mailboxing email addresses.

Tagging an email address is something the owner of an email address can do to make it easier to handle incoming email. It works by adding an extra word to the local part of the email address separated by a special character, such as “+”, “=” or “-“. So, if my email address is steve@example.com, and I’m signing up for the MAAWG mailing lists I can sign up with the email address steve+maawg@example.com. When mail is sent to steve+maawg@example.com it will be delivered to my steve@example.com mailbox, but I’ll know that it’s mail from MAAWG. I can use that tag to whitelist that mail, to filter it to it’s own mailbox and a bunch of other useful things.

In some ways this is similar to recent disposable email address services, but rather than being a third party service it’s something that’s been built in to many mailservers for well over a decade. It doesn’t require me to create each new address at a web page, instead I can make tags up on the fly. And it works at my regular mail domain.

If you’re an ESP it can be interesting to look for tagged addresses in uploaded lists. If it’s a list owned by Kraft and you see the email address steve+gevalia@example.com in the list, that’s a strong sign that that email address at least was really volunteered to the list owner. If you see the email address steve+microsoft@example.com then it’s a strong sign that it wasn’t, and you might want to look harder at where the list came from.

One reason that this is relevant to email address capture is that tagged addresses are something that you should expect people, especially more sophisticated users of email, to use to sign up to mailing lists and that they’re something you don’t want to discourage. Yet many web signup forms forbid entering email addresses with a “+” or, worse, have bugs in them that map a “+” sign in the email address to a space – leading to the signup failing at best, or the wrong email address being added to the list at worst. This really annoys people who use tagged addresses to help manage their email, and they’re often exactly the sort of tech-savvy people who make a lot of online purchases you want to have on your lists.

More on Monday.

What is an email address? (part one)

Given we deal with email addresses every day, dozens or thousands or millions of them, it seems a bit strange to ask what an email address is – but given some of the problems people have with the grubbier corners of address syntax it’s actually an interesting question.

There are two real standards that define what is a valid email address and what isn’t. The most complex is RFC 5322 – Internet Message Format, which describes all sorts of things about the structure of an email, including what’s valid to put in From: and To: headers. It’s really too liberal in what it allows an email address to look like to be terribly useful, but it does provide for one very commonly used feature – the friendly from where the name that’s displayed to the recipient is not just the email address.

AOL and DKIM

Yesterday, on an ESPC call, Mike Adkins of AOL announced upcoming changes to the AOL reputation system. As part of these changes, AOL will be checking DKIM on the inbound. Best estimates are that this will be deployed in the first half of 2009, possibly in Q1. This is something AOL has been hinting at for most of 2008.

As part of this, AOL has deployed an address where any sender can check the validity of a DKIM signature against the AOL DKIM implementation. To check a signature, send an email to any address at dkimtest.aol.com.

I have done a couple of tests, from a domain not signing with either DK or DKIM, from a domain signing with DK and from a domain signing with both DK and DKIM. In all cases, the mail is rejected by AOL. The specific rejection messages are different, however.

Unsighng domain: host dkimtest-d01.mx.aol.com[205.188.103.106]

said: 554-ERROR: No DKIM header found 554 TRANSACTION FAILED (in reply to

end of DATA command)

DK signing domain: “205.188.103.106 failed after I sent the message.

Remote host said: 554-ERROR: No DKIM header found

554 TRANSACTION FAILED”

DK/DKIM signing domain: “We tried to delivery your message, but it was rejected by the recipient domain. We recommend contacting the other email provider for further information about the cause of this error. The error that the other server returned was: 554 554-PASS: DKIM authentication verified

554 TRANSACTION FAILED (state 18).”

As you can see, in all cases mail is rejected from that address. However, when there is a valid DKIM signature, the failure message is “554-PASS.”

As I have been recommending for months now, all senders should be planning to sign with DKIM early in 2009. AOL’s announcement that they will be using DKIM signatures as part of their reputation scoring system is just one more reason to do so.

Ironport response

Last week I posted about a ESP that had a misconfiguration in their Ironport A60s that let spammers use the A60s to relay email to AOL. Earlier this week, Pat Peterson from Ironport approached me to talk about the problem and clarify what happened.

Ironport has provided me with the following explanation.

ESP unwittingly used to send spam

Late last week I heard from someone at AOL they were seeing strange traffic from a major ESP, that looked like the ESP was an open relay. This morning I received an email from AOL detailing what happened as relayed by the ESP.

Read MoreComcast rate limiting

Russell from Port25 posted a comment on my earlier post about changes at Comcast.

Read MoreAOL checking DKIM

Sources tell me that AOL announced on yesterday’s ESPC call that they are now, and have been for about a week, checking DKIM inbound. This fits with a conversation I had with one of the AOL delivery team a month or so back where they were asking me about what senders would be most concerned about when / if AOL started using DKIM.

The other announcement is that AOL, like Yahoo, would like to know how you categorize your outgoing mail stream as part of the whitelisting process.

Both of these changes indicate to me that AOL will be improving the granularity of their filtering scheme. DKIM signing will let them separate out different domains and different reputations across a single sending IP address. The categorization will allow AOL to evaluate sender statistics within the context of the specific type of email. Transactional mail can have different statistics from newsletters from marketing mail. Better granularity means that poor senders will be less able to hide behind good senders. I expect to hear some wailing and gnashing of teeth about this change, but as time goes on senders will clean up their stats and their policies and, as a consequence will see their delivery improve everywhere, not just AOL.

Update on Yahoo and the PBL

Last week I requested details about Yahoo rejections for IPs pointing to the PBL when the IP was not on the PBL. A blog reader did provide me with extremely useful logs documenting the problem. Thank you!

Based on my examination of the logs, this appears to be a problem only on some of the Yahoo! MXs. In fact, in the logs I was sent, the email was rejected from 2 machines and then eventually accepted by a third.

I have forwarded those logs onto Yahoo who are looking into the issue. I have also talked with one of the Spamhaus volunteers and Spamhaus is aware of the issue as well.

The right people are looking at the issue and Spamhaus and Yahoo are both working on fixing this.

Thanks for the reports and for the logs.

AOL and AIM mail

Earlier this week a question came up on a mailing list. The questioner recently started seeing an increase in rejections to @aol.com addresses. These rejections said

Read MoreWhy do ISPs limit emails per connection?

A few years ago it was “common knowledge” that if you were sending large amounts of email to an ISP the most polite way to do that, the way that would put the least load on the receiving mailserver, was to open a single SMTP session to the mailserver and then to send all the mail for that ISP down that single connection.

That’s because the receiving mailserver is concerned about two main resources when handling inbound email – the pool of “slots” assigned one per inbound SMTP session, and the bandwidth (network and disk, and related resouces such as memory and CPU) consumed by the inbound mail – and this approach means the sender only uses one slot, and it allows the receiving mailserver to control the bandwidth used simply by accepting data on that one connection at a given rate. It also amortizes all the connection setup costs over multiple emails. It’s a beautiful thing – it just doesn’t get any more efficient than that.

That seems perfect for the receiving ISP – but ISPs don’t encourage bulk senders to do this. Instead many of them have been moving from “one connection, lots of mail through it” to “multiple connections, a few messages through each”. They’re even limiting the number of deliveries permitted over a single connection. Why would that be?

The reason for this is driven by three things. One is that the number of simultaneous inbound SMTP sessions that a mailserver can handle is quite tightly limited by the architecture of most mailservers. Another is that the amount of mail that’s being sent to large ISP mailservers keeps going up and up – so there are sometimes more inbound SMTP sessions asking for access than the mailserver can handle. The third is that ISPs know that there are different categories of email being sent to their users – 1:1 mail from their friends that they want to see as soon as possible, wanted bulk mail that their users want to see when it arrives and spam; lots and lots of spam.

So ISPs want to be able to do things like accept 1:1 mail all the time, while deferring bulk mail and spam to allow them to shed traffic at times of peak load. But they can only make decisions about whether to accept or defer delivery in an efficient way at SMTP connection time – they pick and choose amongst the horde of inbound connection attempts to prioritize some and defer others, letting them keep within the number of inbound sessions that they can handle simultaneously.

But once the ISP lets a bulk mailer connect to deliver their mail, they lose most of the ability to further control that delivery as the sender might send thousands of emails down that connection. (Even if the ISP has the ability to throttle bandwidth – as some do to control obvious spam – that just means that the sender would tie up an expensive inbound delivery slot for longer).

So, in order to allow them to prioritize inbound connections effectively the ISP needs to terminate the session after a few deliveries, and then make that sender start competing with other senders for a connection again.

So ISPs aren’t limiting the number of deliveries per SMTP connection to make things difficult for senders, or because they don’t understand how mail works. They’re doing it because that lets them prioritize wanted email to their users. The same is true when they defer your mail with a 4xx response.

It might be annoying to have to deal with these limits on delivery, but for legitimate bulk mail senders all this throttling and prioritization is a good thing. Your mail may be given less priority than 1:1 mail – but, if you maintain a good reputation, you’re given higher priority than all the spam, higher priority than all the email borne viruses, higher priority than all the junk email, higher priority than the 419 spams. And higher priority than mail from those of your competitors who have a worse reputation than yours.

DKIM "i=" vs "d=" and Reputation

This really should be part seven of a twelve part series or some such as it deals with an aspect of DKIM that’s really important, but is way down in the details of implementation. (dkim.org is a reasonable place to start for a general overview of DKIM).

There’s an apparently endless thread on the DKIM-SSP spec development mailing list at the moment about the differences between two fields in a DKIM signature that could be used to tie a senders reputation to. Several ESP delivery folks asked me to explain what everyone was talking about, and this post is a first cut at that.

“i=” vs “d=”

There are two possible fields in a DKIM signature that could be used to identify the sender of a message, and so to tie a sender history and reputation record to. They are the so-called “i=” and “d=” field, from the syntax used to include them in the signature.