During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. — Richard Feynman

IP and Domain Warming

It’s common practice that when you change the IP address you’re sending your mail from you don’t just dump all your mail onto the network at once. You send just a tiny little bit of email, then a bit more, then gradually ramp up your volume until you’re sending at your usual level.

Similarly when you start sending from, or authenticating with, a different domain. It’s common practice, and it’s just what you do, otherwise you’ll be cursed with poor delivery from the new IP address or the new domain.

But why?

Email isn’t passed directly from person to person. It’s mediated by the software being run by the email sender and the mailbox provider. At the mailbox provider end of the transaction the most obvious piece of software is their spam filtering automation.

Spam Filters

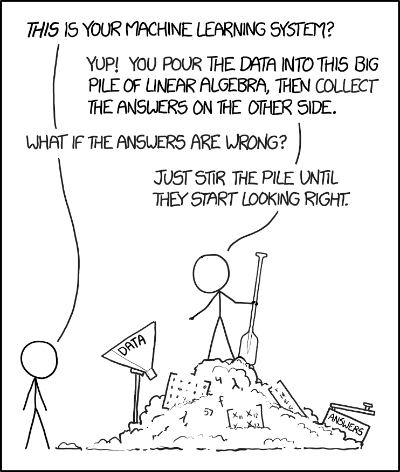

Spam filters are not simple pieces of software. Many of them are complex systems using machine learning1 to identify streams of mail, track their behaviour over time and recipients’ response to them. They interpret the policies of the mailbox provider to optimize recipient happiness. That sounds incredibly futuristic and shiny. But they’re likely also composed of poorly understood configuration for special cases, changes layered on changes over time, manual overrides, perl scripts, bitrot and gaffer tape and chewing gum – so maybe your mental model of spam filters should be a bit closer to Mad Max meets Dr Who than to Star Trek. Something with rust, welded plates, valves and flashing lights and big levers.

It’s likely that very, very few people completely understand how it works and what exactly it does.

It’s possible that nobody does.

When you’re delivering email, this is the system you’re negotiating with. It’s just software, but it has complex – and not obviously deterministic – enough behaviour that it’s hard not to anthropomorphise it.

The spam filter knows that there are good senders and bad senders. It knows that it’s easy and cheap for bad senders to change their identity, so it doesn’t really trust new identities. But it also knows that there are lots and lots of low volume senders out there sending wanted email, so it will deliver mail that looks reasonable from those low volume senders, while keeping an eye on it and the responses of users to that mail. It also knows that spammers will often pretend to be many independent low volume sources of email.

It knows that spammers often have a business model of sending a bunch of spam to as many users as possible, then moving on. And it knows that they’ll sometimes spin up a new VPS to do that, but also that they’ll sometimes compromise an existing source of email in an attempt to take advantage of its existing reputation. If there’s a sudden increase in traffic from a source it knows that might be a sign of bad actor, and the filter will perk up it’s ears and start throttling or blocking that mail, while waiting for it’s users – humans are so, so slow – to see the email it has delivered and respond to it.

It’s doing all this in real time, at a ridiculously large scale, while running on relatively small amounts of CPU and storage. Some things that seem easy for a hundred emails a day get harder at tens of thousands of emails a second. It won’t be able to look at every email in depth, it’ll be sampling and using fast heuristics and trying to keep everything flowing as it keeps the balls it’s juggling in the air. It can’t possibly remember every email, so it’s keeping track of very abbreviated metrics tied to mail stream identifiers and even those won’t be remembered for long unless a sender does something really memorable. It may remember that it likes you or doesn’t like you, but it doesn’t remember why.

It’s jumpy and suspicious and protective of its users and it really doesn’t like sudden changes.

A Diplomatic Conversation

We talk about “warming up” an IP address or domain, and it’s useful language to distinguish between a warm source of mail and a cold one. But it’s a bit misleading because what we’re really doing isn’t gradually increasing the warmth of a sending IP – rather we’re having a conversation with the spam filtering system at our recipients MX, introducing ourselves, showing it who we are as a sender, and convincing it that its users will like the email we’re sending.

By trickling mail in slowly it gives the spam filter time to compare our mail stream with other mail that’s being delivered – are we really sending slowly, or are we a snowshoe spammer dividing our mail streams across thousands of sources? Are we really a new mail stream, or are we part of an existing stream moving to a new IP or domain?

We’re building trust as we do this, persuading the filter that we’re probably not a wildly illegitimate spammer, or an infected windows machine. It’ll deliver our mail, and be happy with us sending a bit faster.

It’ll see that our mail stream is coming from a new source, and the volume from that source is reaching a level that’s interesting. Maybe it’ll sample a few of the emails, and look at the content, or even reach out and fetch some linked content to see what that looks like.

By now we’ve given the filter a chance to see the reactions of some of the recipients. As it sees how users respond to our email (or how they’ve responded in the past to mail like ours), we give it a chance to better understand who we are, and what sort of mail we send.

It’s now seen enough deliveries that it has some idea of who our audience is. Are we sending to recipients who, well, exist? Are we sending to people who seem to have liked mail similar to ours in the past? Are we sending to inauthentic recipients who appear to accept mail only to game filters? Are we sending to recipients who haven’t logged in in six months? Are we sending to lots of people who only use IMAP, not web or app to read mail?

Waiting a bit longer, the filter starts to see more humans look at the mail that’s been delivered. Have any of them marked it as spam? Have a lot of them marked it as spam? Is it Bad Mail?

If it’s still not sure then it may need some more time. Maybe it’ll keep watching the mail you’re sending, as long as there’s not too much. Maybe it’ll start deferring delivery attempts. Maybe it’ll deliver some of the mail to the inbox and see who marks it as spam. Maybe it’ll deliver some of it to the spam folder and see if anyone goes to move it back to the inbox.

Eventually the filter will have been able to make a preliminary decision about who we are and what sort of mail we send. If it doesn’t like it, it’ll start delivering it to the spam folder. If it does like it then it’ll deliver it to the inbox. But it’s still going to be wary – maybe a spammer knows how spam filters works, and they’ve cosplayed as a good sender to this point and now they’re going to blast out their real content. It still doesn’t like rapid change, and won’t until it really trusts the mail you send.

I’ve shown you who I am

All this means that warming up IPs or domains – like many deliverability practices – only really works for senders who send mail people want to people who want to receive it.

If you’re sending mail that people don’t want, whether it be crappy customised t-shirt spam, or B2B cold outreach mail, then it doesn’t quite work the same way. You can follow the same mechanical steps, build up your volume gradually, starting with your few engaged users but then at some point your mail stops being delivered. You’ve gone through the process to explain who you are and what mail you send to the spam filter – and the spam filter believes you, and so blocks your mail stream or your IP or your domain.

You’ve done everything right. But no airplanes land.

This is why you hear so many complaints about “those deliverability people” from the bad senders. That we don’t bring any value, that we just want to stop them from sending mail, that what we do doesn’t work, that we just pay off ISPs to let mail in. That, instead, marketers should just send more email.

What we do doesn’t work for them, because of who they are, and because they can’t hide who they are. All that’s left for them to do is filter evasion.

- It’s like Artificial Intelligence, but more of an actual tool and less a VC scam. ↩︎

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts